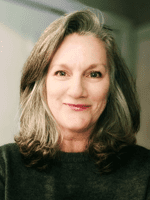

The stars have aligned. Like Icarus of Greek mythology, Ann Davies has always wanted to get closer to the sun, the star nearest the earth, ever since she was a child studying the skies in northern Wales with a basic telescope. But, unlike Icarus, Davies won’t burn her wings. In fact, with her recent appointment as chief operating officer of Lightsource bp, a joint venture between the two companies, she continues to fly ever higher up the ranks at bp.

“I remember looking up at the sky and being absolutely fascinated. At the time I was growing up, the shuttle program in the U.S. was underway. This was before the age of the internet and I used to write letters to NASA. What captured my imagination was how small we were in this universe and how limitless the human imagination could go. That’s really what got me interested and later prompted me to study physics and maths, and chemistry as well, at school up to a higher level. I was just desperate to understand the language of the universe.”

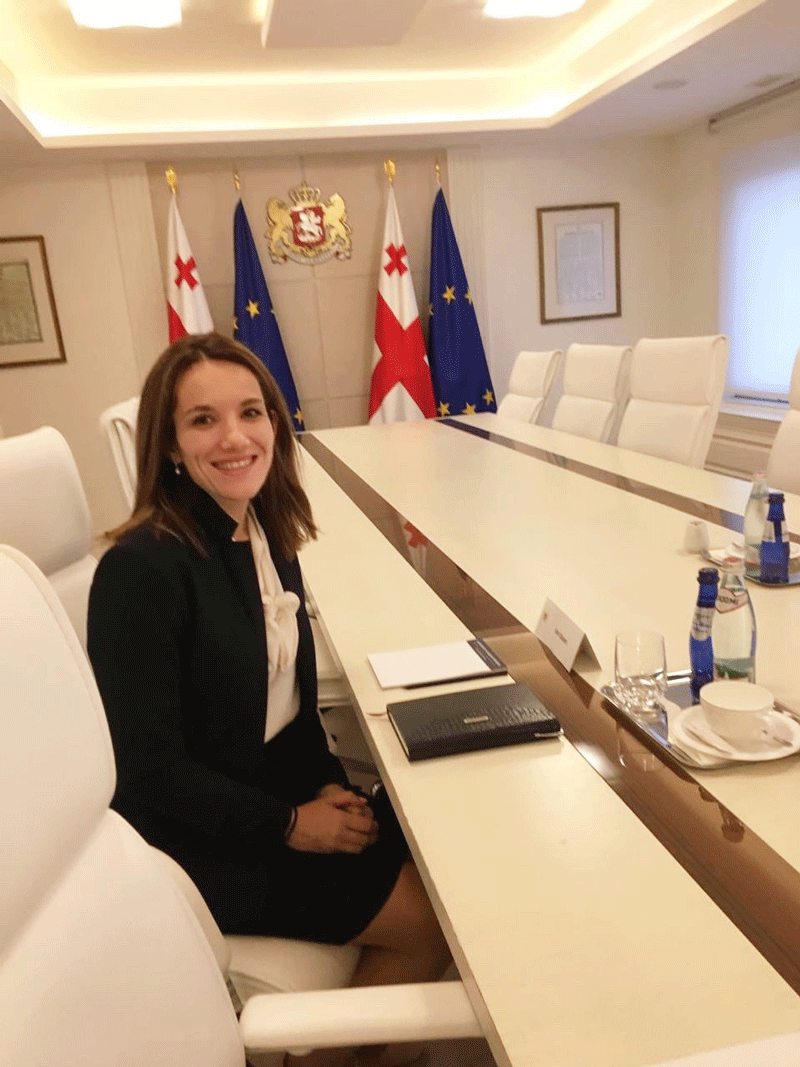

It was that fascination that led her to enter a competition in the U.K. devising an experiment to go on the international space station. She won the competition and was awarded the grand prize: astronaut training in Belgium. At the time, the European space agency was in the process of moving its core astronaut training from Brussels to France, so she had the opportunity to train, including participating in shuttle simulation, with other winners across Europe. That experience had such a profound impact on Davies, it was one of the reasons she chose to study physics at Oxford University.

“I had this chief passion for astrophysics, as well as space science. The more I learned during the four years I was at Oxford, the more my curiosity with the world expanded. One could say I held an exuberant childish dream, but I was proud of that. Children are gifted with limitless curiosity, and I believe, as adults, we should cherish and protect that childlike curiosity. We shouldn’t be afraid to ask silly questions and fill our dreams with big ambitions. I love that children have big dreams and big curiosity. The more I learned at university, the more I realized I didn’t know about the world.” This, in turn, created a greater interest in engineering. “I was fascinated by using physics to solve real problems in the world.” Davies took on engineering-related internships – one with the Ministry of Defense in the U.K., and another with bp – and says, “The work that bp did really sparked my interest in the energy industry. And when they offered me a job after university, I was keen to take it.”

Within 15 years, Davies had worked her way up to her current role as one of the rare female chief operating officers – in addition to Jannicke Nilsson at Equinor – of a major energy company. How was she able to rise to the C-suite in half the time it takes most men or, much less often, a woman?

It has been documented that women in male-dominated industries struggle to get critical time in the field, which can help them later in their career, but Davies didn’t allow that to happen. “I started going to the field very early on in my career and I always pushed to go because it’s work imagined versus work done. As an engineer, you are using your skills and knowledge to imagine work; you’re putting it down on paper for workers to execute, but unless you spend time witnessing the execution and understanding how work imagined translates to work done, it’s very difficult to continue your learning.”

With that in mind, Davies also insisted on going offshore. “My first year at bp, I was always trying to get on the rig and, as a woman, it can be quite difficult because men and women aren’t supposed to share a cabin. By going out, you’re sometimes taking the space of two people because it’s very rare that you have an even number of women.”

With that in mind, Davies also insisted on going offshore. “My first year at bp, I was always trying to get on the rig and, as a woman, it can be quite difficult because men and women aren’t supposed to share a cabin. By going out, you’re sometimes taking the space of two people because it’s very rare that you have an even number of women.”

She was so persistent, “bp sent me to Canada,” she says, laughing. At the time, bp had a business called North America Gas with thousands of wells throughout Alberta and British Columbia. Arriving in Canada, Davies says, “They gave me a pickup and a laptop and off I was.” She spent her time in the field – “work imagined, work done” – writing programs, engineering, witnessing the execution and learning her trade as well as the business. “Those were some of the best days of my career because I really enjoyed being on the learning curve, but I also really enjoyed being out in the wild, getting to know people.”

Having built competence in operations, which Davies credits to her time in the field, she returned to the U.K., and spent the next six years going offshore regularly to platforms in the central North Sea. Eventually, she became a well site leader on one of bp’s light well intervention vessels that worked in the Atlantic and also worked on semi-submersible rigs. “I was on night shift in charge; I was known as the company man, which was quite unusual for a young woman.”

Davies says it was still rare to see a woman on the installations in the mid-2000s, but being young had its challenges, as well. She was respectful of the fact that some of the people – nearly all men – she was working with had spent their whole careers, spanning two or three decades, offshore and acknowledges they were not expecting to see a young woman, especially in a supervisory role.

Davies says it was still rare to see a woman on the installations in the mid-2000s, but being young had its challenges, as well. She was respectful of the fact that some of the people – nearly all men – she was working with had spent their whole careers, spanning two or three decades, offshore and acknowledges they were not expecting to see a young woman, especially in a supervisory role.

Her approach was, “You don’t know what you don’t know, so always be curious. Accept the fact that my role is not to be the expert; my role is to ask a lot of questions and create the right environment for the team to perform and to deliver safely and to bring people together.” She had put in the work over the course of her career to strengthen her engineering expertise and, in being on a number of different operational sites around the world, had focused on her leadership skills, which she says, “Meant I had something to give, I had a role, and was willing to stand up for myself, but also very willing to listen. When you work in a hazardous environment with high-pressure hydrocarbons, the importance of acute listening is crucial. If you don’t listen, you miss one critical piece of information that can be the difference between a good decision and a bad decision. Spend time getting to know people, to understand the dynamics of the team, to trust people, and eventually the label of ‘young’ or ‘woman’ gets dropped and they see you for the experience and the skill you bring.”

It was a rare occasion that she got to work with another woman. As she became more experienced, she tried to mentor and support the few women she encountered offshore and looked for opportunities to make things better for women, such as improving the facilities.

By the time Davies had worked her way up to superintendent – a team leader for wellsite leaders – she was working both onshore and offshore in bp’s Valhall and Ula fields in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea, where she was impressed to see quite a few women in technical and operational positions. “I tried to learn as much as possible from Norway about what it was they were doing well to attract more women into operational roles and what I discovered was, it is something that starts from childhood. Both mothers and fathers take leave to care for their children, so kids are used to both parents working. I also noticed excellent childcare facilities everywhere, less marketing of boys’ toys versus girls’ toys, and outdoor time is ingrained in the culture, regardless of the weather. Girls and boys learn early on that they are not limited in their society and are encouraged to pursue their intrinsic passion and interests.” That ability to make the connection between family and work is perhaps one of the defining characteristics of Davies’s approach to leadership.

In thinking back to her own career trajectory which led to her role as COO, Davies says her insistence on gaining field experience centered around “work imagined, work done” and wanting to take her business from two dimensions on paper to three dimensions and what happens in reality. “That really helped my operational understanding and, yes, they are useful skills when you advance to a COO position, but what I probably gained the most from spending time in the field was actually learning about leadership.”

“When I look back as to when I really evolved as a leader, I take myself back to those times offshore when I had to make difficult decisions, when I had to influence people, when I was making decisions on safety and environmental protection. Bringing a hundred people from different backgrounds together, sometimes as a minority myself, as a female, having to lead and inspire others is when I developed as a leader.”

In thinking about the COOs of the future, particularly women and other minorities, and how industry develops them, Davies acknowledges that one way to get those leadership skills is through having field experience, just as she did, but she doesn’t believe that is the only path to the C-suite. She urges companies to think about their talent and how they are developing leadership skills within their population across a diverse group of people because, in some circumstances, it can be easier for one group of people to gain that field experience than it is for others. Davies believes companies can correct that by implementing clear development plans for people that include not just technical expertise, but also leadership acumen, by giving men and women the opportunity to lead early on in their careers.

In thinking about the COOs of the future, particularly women and other minorities, and how industry develops them, Davies acknowledges that one way to get those leadership skills is through having field experience, just as she did, but she doesn’t believe that is the only path to the C-suite. She urges companies to think about their talent and how they are developing leadership skills within their population across a diverse group of people because, in some circumstances, it can be easier for one group of people to gain that field experience than it is for others. Davies believes companies can correct that by implementing clear development plans for people that include not just technical expertise, but also leadership acumen, by giving men and women the opportunity to lead early on in their careers.

“I think that’s what really made the difference for me and I would love to see more women in executive positions. I’m a scientist – and the science is clear – diverse teams work together and make better decisions. You’ve actually got to remember why you want diverse teams in the first place. Not only does it produce a better output, but it also contributes to a fair and just world. I have two daughters myself and I hope that one day they could compete equally for whatever role they would be interested in doing.”

Lightsource bp’s executive team in London is comprised equally, 50 percent men and 50 percent women. Davies, who has spent so much of her career being one of few, if not the only woman, says, “You can feel the difference when you’re in a room that is equally gender-balanced, so it’s something companies need to focus on, but I think the way to do it is look at your leadership development pipeline and make sure you’re creating a company that whatever background you’re from, wherever your gender, your ethnicity, that you’re able to be the best that you can be within that company. If you get inclusion right and have diversity at the top, then equity should sort itself out.”

Davies speaks slowly and thoughtfully when she says, “I was also acutely aware of these massive changes that were going on in the world, but also I was looking at my kids and thinking about what the future is for them, what the world is going to look like for them when it comes to energy.” As if on cue, she says, “One of my daughters just walked in” [child’s voice in the background]. Davies responds, ‘Hi, love, Mummy’s busy now, I’ll be with you in a minute.’ Returning to the interview, she explains, “She came in to give me a big hug.” Laughing, we agree this is the new reality of working from home.

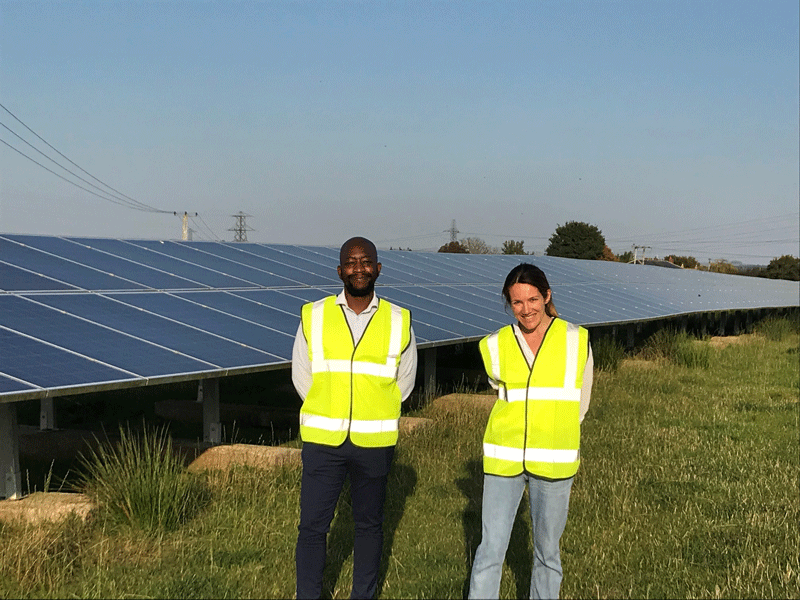

Without missing a beat, Davies continues her thoughts. “One thing I’m quite passionate about is, there is no such thing as bad energy or good energy.” While she considers energy academically interesting, she also sees it as purpose-fueled, something she personally finds engaging and uses to motivate others to think about energy as a career. “Energy is a bit like an infinite game. We have a responsibility in the business, but also governments around the world have a responsibility to use our energy incredibly carefully, ultimately to advance a cause, and protect our planet and protect people, so I just find it hard to imagine anything that can be more exciting on this planet.” She adds hastily, “I’m excluding space travel because that’s not on this planet!” and laughs softly. “There’s never been a more exciting time to get into energy because we are in the process of a revolution in energy. At bp, we use the term ‘Reimagine energy.’”

“Any scientist or engineer out there wants to solve problems; that’s probably why they picked science or engineering in the first place. Some of the biggest problems we have on this planet relate to energy. I’m a Millennial and people from my peer group, especially, are worried because they’re looking at the next 20 years and how they can adapt their skill sets to the transition. It’s important, as energy companies, to emphasize that we’ve all got a part to play in the energy challenge. There’s so much to learn from each other – whether it’s in oil or gas or renewables or the policy side. This is one big issue to solve and it’s going to take time, it’s going to take patience, and it’s going to take action, and we have to work together for our future.”

Photos courtesy of Lightsource bp.

Reprinted by permission. This article originally appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of OILWOMAN Magazine.

Rebecca Ponton is the editor in chief at U.S. Energy Media and author of Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. She is the publisher of Books & Recovery digital magazine.