Falling into a mud pit as a child in Oklahoma didn’t deter Dewey F. Bartlett, Jr., from going into the oil and gas industry; in fact, it may have helped cement his decision, although it took him a while to come to that realization.

As the tale goes, in the late 1950s, Bartlett had accompanied his father, a geological engineer, who, along with Bartlett’s paternal grandfather, worked in the industry, to a well site, which he would do on occasion. Bartlett recalls wandering around while his dad talked with some of the workers on site.

“There was a hole dug into the ground where the drilling mud accumulated and then eventually was pumped out and disposed of – and I ended up falling into the mud pit, which was full of mud and real dirty,” Bartlett says.

“My dad had a brand new company car and didn’t want me sitting in it with wet, muddy pants. I had to take off my pants and I ended up riding back home in the trunk of the car,” he recalls laughing. “I remember the trunk had a two-way radio in it that they used to talk to the engineers and other personnel. Back in those days, there were no transistors. It was warm in the trunk because the electronics were located in this big box and the tubes put off a lot of heat … Falling into the mud pit was my very first memory of the oil business.”

The Grand Lake Years

After graduating in 1969 with a B.S. in Accounting from Regis College in Denver, Colorado, Bartlett went on to earn an MBA in Finance from Southern Methodist University (‘71) in Dallas, Texas. While he was initially intrigued with the idea of becoming a stockbroker, life took him in other directions and he became involved in real estate and residential construction for a period of time.

His father, Dewey F. Bartlett, Sr., governor of Oklahoma (1967-71) and later senator (R-OK; 1973-79), was interested in cattle ranching and bought quite a few acres of land in northeast Oklahoma, where he built a house on a hill next to Grand Lake. (Bartlett says his mother was always supportive of his father, but she wanted a place where they could get away from the pressures that came with the job of managing the state’s affairs.)

When the two men who were running the cattle ranch quit, Bartlett and his brother offered to move to Grand Lake. “We didn’t know anything at all about cows,” he says laughing, “so that led to a lot of interesting learning experiences with cows and bailing hay and that sort of thing. That lasted a couple of years and then my uncle died … and that curtailed my career in the cattle business.”

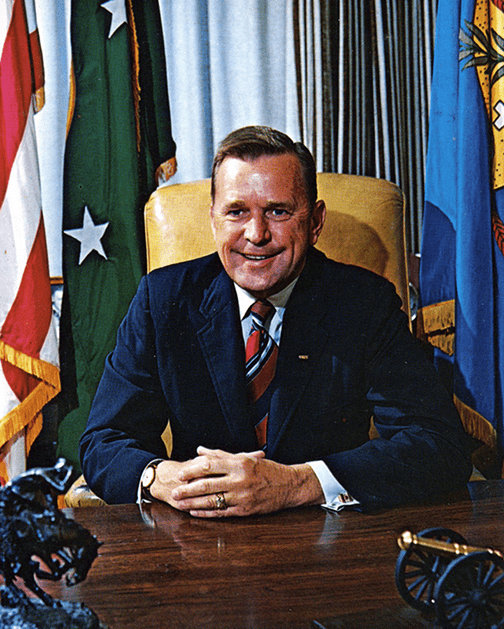

U.S. Senator Dewey Follett Bartlett, Sr.

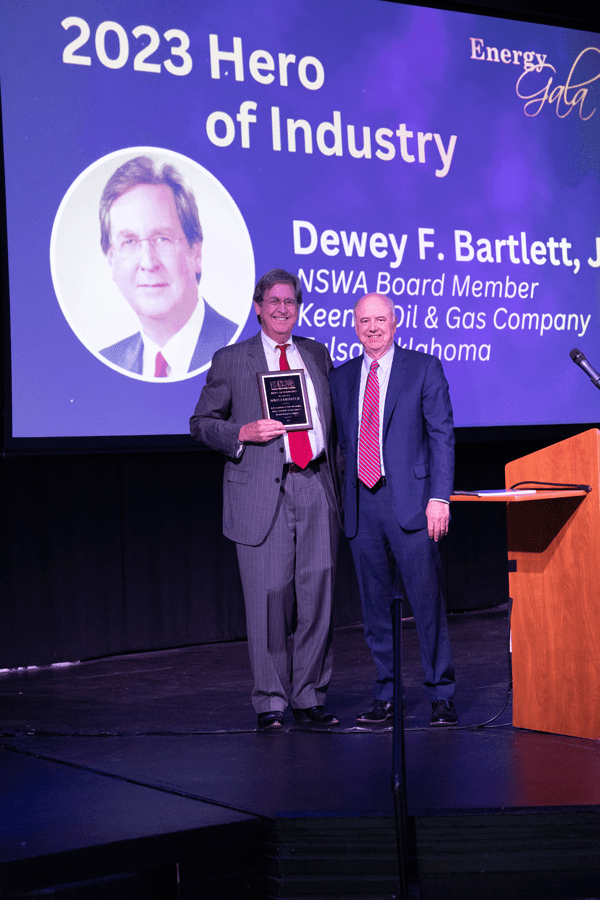

Keener Oil & Gas Company, named for the Keener sands, has undergone variations in the name as it has changed leadership. When Bartlett was about 30, the ownership of the company belonged to his father, his father’s older brother, their mother, and a few cousins. “My uncle – my dad’s brother – owned the largest piece of it. When he died, he had no heirs, so he left his interest in the company to me, my brother, and sister. I was made the executor of his estate, so I was essentially put in charge of the company. I knew then that I was going to be in the oil and gas business.”

It was also around this time that Bartlett’s father, Dewey Follett Bartlett, Sr., was elected to the U.S. Senate (R-OK) – having previously been the governor of Oklahoma from 1967 to 1971 – serving one term from 1973 until shortly before his death in 1979. The Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) initiated the first oil embargo in October 1973, as Senator Bartlett began his tenure in Congress, with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposing a full embargo against the U.S. and other countries in December of that year.

“They cut back their [monthly] production by five percent, a small amount, but they controlled the price of oil at that point, and eventually that sent most of the world into a recession,” Bartlett recalls. By 1974, the price of oil had nearly quadrupled.

Senator Bartlett and Senator Sam Nunn (D-GA) served together on the Armed Services Committee and Sen. Bartlett stressed to Sen. Nunn and the other members of the committee the importance of supporting independent oil and gas companies, says Bartlett, “Because, even though [the U.S. was] importing a huge amount of oil, if we were not able to supply much oil to the country, we would be over a barrel – literally.”

Despite being on different sides of the aisle politically, Bartlett says his father and Sen. Nunn “developed a relationship and collaborated to find common ground in order to make things work better for the country.” To that end, the two senators embarked on a trip to Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries. “No one had done this before,” Bartlett points out. “No one had gone to try to talk to them.” The senators also visited a few of the U.S. overseas military bases.

“They found out very quickly that if the bases did not have access to oil and its refined products – which at that point they imported from the United States – they couldn’t fuel their airplanes, they couldn’t fuel their jets, and they couldn’t fuel their ships. It became very apparent to Sen. Nunn that having domestic access to the production of oil and natural gas was extremely important to our national security.”

Sen. Bartlett and Sen. Nunn cowrote a report emphasizing the necessity of supporting independent oil and gas producers because, at some point in the future, the world would go to war over access to crude oil. “And that particular statement became true,” Bartlett observes. “That was the background I had on the significance of the oil business.”

The Halliburton Years

Once he had made the decision to continue the family legacy and work in the oil and gas industry, Bartlett sought his father’s counsel about what he should do and Bartlett says his dad gave him “great advice” and that was to go to work in the field and learn the business from the ground up – literally. At that time, Halliburton had a field office in Enid, Oklahoma, and he was able to secure a job there as an oil well cement operator.

“Halliburton had a terrific training program,” Bartlett says, “and probably the best thing I learned, besides the vernacular of all the different things that are being put together or are part of the production and completion process, is how to talk to people. I let them know I was a good, decent guy that liked to work hard. I wasn’t just some rich guy’s son that was getting a job [handed to him]; I really had to prove myself and I was very proud of being able to do that.”

Although he had worked two summers as a teenager at one of Tulsa’s two refineries moving barrels of oil on a cart and offloading them onto a railroad car or semi-truck, it was the two years with Halliburton that convinced him he had a future in the oil and gas industry. Bartlett dabbled in other types of employment and says, “I waited until I was 40 to take over the reins and become the real person in charge [at Keener].”

Mayor of Tulsa

Mayor of Tulsa

In his early 60s, Bartlett made his foray into politics, becoming the 39th mayor of Tulsa, in somewhat of a full circle moment in history, going back to his father’s time in the Senate.

“When I was mayor (2009 – 16), unfortunately, legislation had [previously] been passed that did not allow for the exportation of crude oil.” In response to the oil embargo, legislation was enacted in 1975 to ban the export of crude oil. The ban was not lifted until 2015 – 40 years later – and shortly before Bartlett left office. A study published in 2020 by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that crude oil production nearly doubled from 2009 to 2015, a period which covered almost the entirety of Bartlett’s mayoral terms. (With the passage of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 in December 2015, the ban was finally lifted.)

“It was a protectionist type of legislation,” Bartlett says, “because, at that point, the industry was supporting more than could be sold and so we were awash with oil, so to speak.”

“When my father was in the Senate, he authored legislation that decontrolled the price of stripper oil. That was a huge deal because the domestic price of stripper oil was much lower than the worldwide so-called free market of crude oil. That really had an influence on my interest in helping spread the gospel, so to speak, on the significance of independent domestic oil and gas companies, how many people they can employ, how much capital is expended, the amount of oil and natural gas that is discovered, etc.”

As mayor, Bartlett visited Washington, DC, several times a year and, on one of his trips, he ran into a lobbyist who, along with other lobbyists, was pushing for the ban to be lifted on the export of natural gas. At the time, Tulsa had the second highest number of people directly employed in the manufacturing of oil and gas products than any other city in the country except Houston, so Bartlett says, “It was a big deal. We had a huge [impact on] economic development and employment. All of that was very significant.”

Taking a page out of his father’s political playbook, after Bartlett got back home to Tulsa, he contacted about 20 mayors – both Republicans and Democrats – and a few governors that jointly signed a letter he had created that was directed to then-Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz. In it, the mayors and governors explained that they represented a sizable number of companies, manufacturers, and people employed by the oil and gas industry, and how significant the industry was for their cities. Furthermore, the letter explained that the curtailment of the exportation of natural gas had a detrimental effect on the price of natural gas.

Several months later, the Obama administration agreed to allow the exportation of natural gas by approving natural gas export terminal sites. “I’m not saying that my letter was the reason why,” Bartlett muses, “but I will take credit for catching somebody’s attention.”

Sage Advice

The pathway to Tulsa began with Bartlett’s grandfather’s energy interest in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in the late 1800s. Keener Oil & Gas is beginning its fourth generation of leadership over the past 100 years. After nearly 40 years at the helm, and as the next generation moves into leadership, it’s likely that Bartlett will share the same advice his father gave him: “The best thing you can do is spend time in the field.” Bartlett adds, “In other words, where the work is done, and learn that part of the business because, as [my dad] said, that’s where the money normally is made or lost.”

To learn more, visit Keener Oil & Gas.

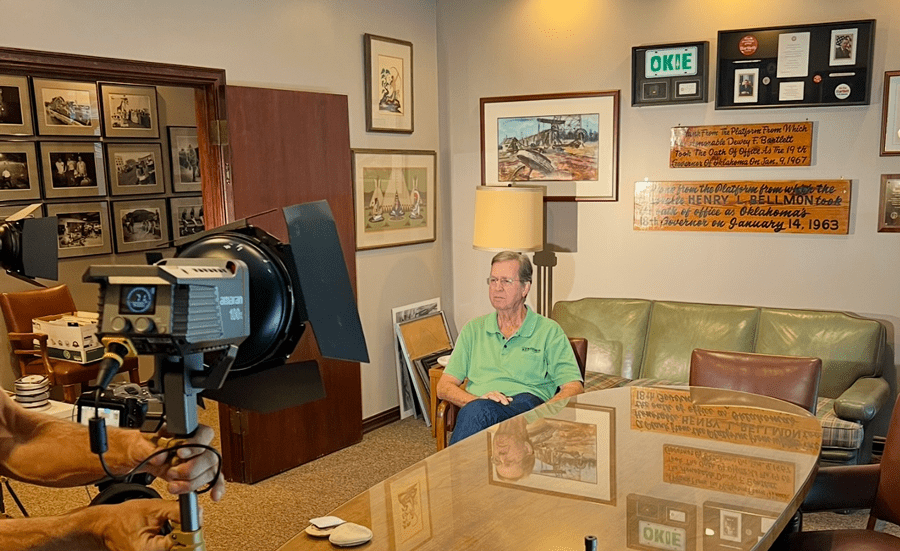

Bartlett is featured in a new mini-documentary entitled Route 66: The Road of Royalty. He talks about the importance of the energy industry and his family’s energy history in the development of Route 66. Mark A. Stansberry is the producer; David A. Guest and Robyn Guest are executive producers. For more information, contact Stansberry at markastansberry@gmail.com.

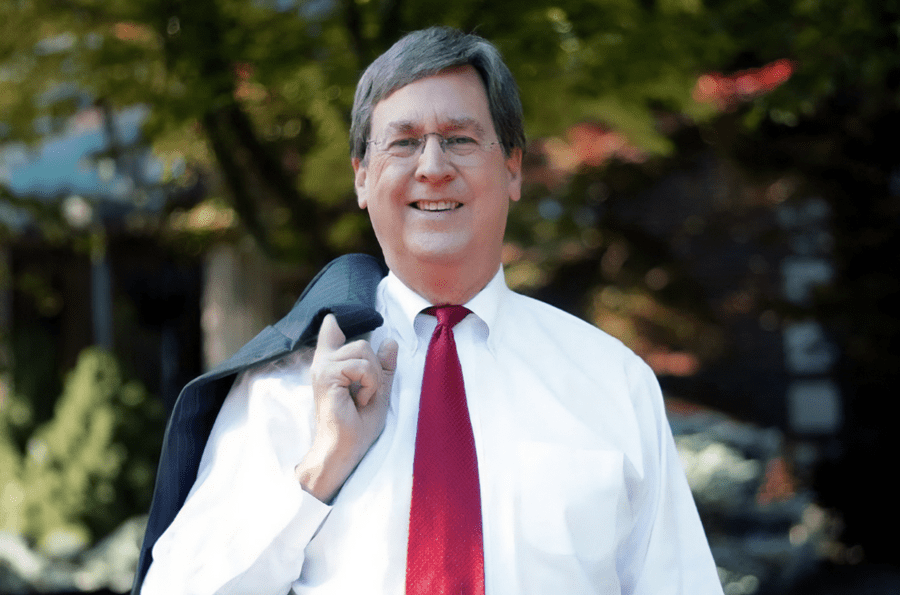

Headline photo courtesy of Tulsa World.

Rebecca Ponton is the editor in chief at U.S. Energy Media and author of Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. She is the publisher of Books & Recovery digital magazine.

Mark A. Stansberry, energy advisor and corporate development strategist, has been a columnist and contributor for Energies Media since 2014. He is the author of America Needs America’s Energy: Creating Together the People’s Energy Plan and the host of the National Energy Talk podcast. Stansberry served as U.S. Senator Bartlett’s intern/staff member from 1975-76, and led Senators Bellmon and Bartlett’s State Youth Conference in 1976. Stansberry can be contacted through his website.