Paula McCann Harris, Former Global Director, Schlumberger

Fresh off a trip from Egypt . . . Texas, that is . . . where she had been visiting her parents a mere two hours before, Paula McCann Harris is right on time for our Zoom chat. Wearing stylish, oversized tortoiseshell glasses, she gives off a very Oprah Winfrey vibe.

Harris, in fact, was in the Middle East in January 2020 at the start of the global pandemic when companies began recalling employees from foreign countries and implementing travel restrictions. After spending a week in India, she traveled to Qatar and then Oman in her role as Schlumberger’s Global Director, giving presentations to management teams and some of the company’s 85,000 employees worldwide on the direction the company is going with regard to the energy transition. As she prepared to give her final workshop, the manager announced that all employees had been grounded and would need to stay in the country they were in. Upon hearing the news, Harris thought, “I’m leaving in the morning!” Fortunately, she was able to catch her flight and return to the U.S., where business was conducted as usual, for the most part, until March.

As the pandemic continues, each of us has to weigh the pros and cons of traveling anywhere but, for newly retired Harris, who retired in May 2020 after 33 years with Schlumberger, the benefits of spending time with her parents outweigh the risks. The enforced slowdown has given her clarity about one thing, though: “I’m too young to retire permanently!”

Instead, she refers to it as being “on hiatus” and sees it as an opportunity to do the things her busy schedule as Schlumberger’s Global Director – a job that necessitated traveling all over the world – didn’t allow her to do. In addition to enabling her to spend more time with her parents, “I get to spend so much time in my backyard gardening and swimming daily, which I never did before. I’m taking care of my body, bicycling and going to the gym every day.” She has discovered, much to her surprise, that she relishes having the opportunity to focus on herself. “I’m enjoying it!” she says exuberantly.

How much she actually has slowed down is debatable. Even before retirement, Harris was a dedicated volunteer, serving on the boards of numerous non-profits, including the Houston Children’s Museum, the Petroleum Club of Houston and Energized for STEM Academy Charter School. Her passion – engaging children, particularly girls, in the STEM subjects – had a direct correlation with her work. Now that she is retired, she finds herself putting in the same amount of time, if not more, volunteering.

“I found myself coming home from the school at 11 o’clock one night and I said, ‘Wait a minute. If you’re putting in these kinds of hours, don’t you want compensation?’ But what I didn’t want was to have to get up the next morning and do it again!” she says laughing. While volunteering is still very much a part of who Harris is, she cautioned herself to find a better balance, “Because I will get very intense and take it to another level!”

She wasn’t always that way, though. In a story that has become part of her personal lore, she says she was such an “acquiescent kind of kid” that when her father, Paul, whom she’s named after, told her she could go to college wherever she wanted and be whatever she wanted, but the only education he was paying for was a petroleum engineering degree from Texas A&M University, she did as she was told! Growing up, she says, “I’d never met an engineer. I had never gone to a camp or read a book and didn’t even understand what engineering was,” but every Sunday she and her dad, a former sergeant with the Houston police department and later an investigator with the DA’s office, would read the Houston Post together and discuss the highest paying careers; petroleum engineering was always number one.

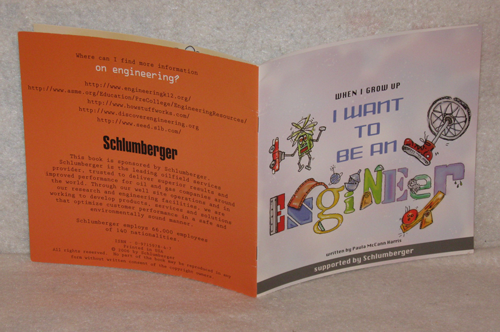

That lack of exposure to – or even basic knowledge of – engineering would later be the catalyst for Harris writing a children’s book, sponsored by Schlumberger, about the way engineers can make the world a better place for everyone. Her own lack of understanding growing up “is the reason I spend so much time with the books and workshops and summer camps and programming to introduce kids to engineering.” Since its release in 2004, thousands of copies of When I Grow Up, I Want to Be an Engineer have been given to children around the world and the book has been translated into Spanish, French and Russian. During her time with Schlumberger and with her ongoing community and volunteer work, she places special emphasis on creating awareness of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) for lower socioeconomic kids of color and girls, saying, “That’s my thing in life.”

That lack of exposure to – or even basic knowledge of – engineering would later be the catalyst for Harris writing a children’s book, sponsored by Schlumberger, about the way engineers can make the world a better place for everyone. Her own lack of understanding growing up “is the reason I spend so much time with the books and workshops and summer camps and programming to introduce kids to engineering.” Since its release in 2004, thousands of copies of When I Grow Up, I Want to Be an Engineer have been given to children around the world and the book has been translated into Spanish, French and Russian. During her time with Schlumberger and with her ongoing community and volunteer work, she places special emphasis on creating awareness of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) for lower socioeconomic kids of color and girls, saying, “That’s my thing in life.”

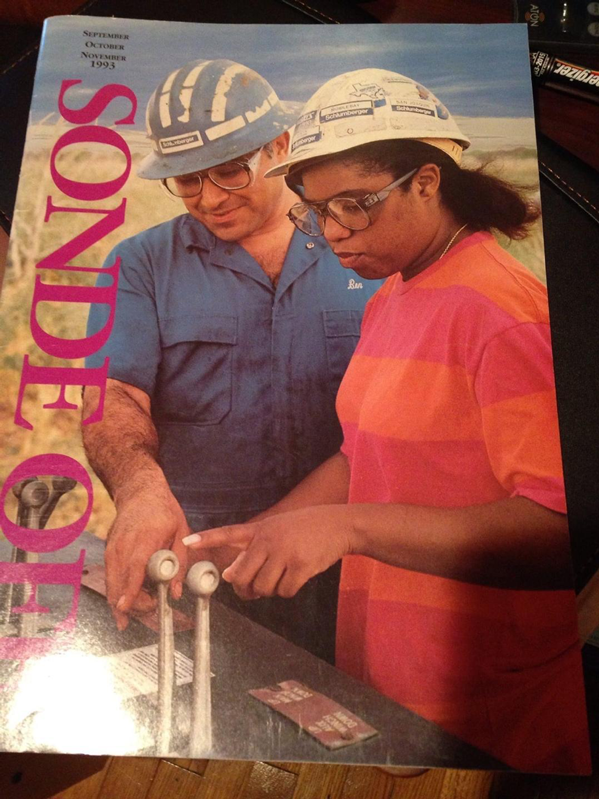

Harris wants these young people to bring diversity to the engineering classrooms and to the workforce that didn’t exist when, acquiescing to her father’s wishes, she enrolled in Texas A&M as a petroleum engineering major in 1982. “It was tough and it was hard. I was always the only girl and the only African American.” She said the harsh environment was good preparation for later working in the male-dominated oil and gas industry and, specifically, offshore. She also was introduced to the cyclical nature of oil and gas. She had an internship with Mobil Oil and a scholarship from Chevron. “I’m working for these big companies and being sponsored by them and the bottom falls out in 1987.” Mobil decided not to hire any of its interns at the time and Chevron elected not to hire its scholarship recipients. After discovering that Schlumberger was hiring a small number of engineers for a training program, she went to Lafayette, Louisiana, and applied.

“I literally cried after my interview. I said, ‘I don’t want to work for a service company; I want to work for a big oil company.’ And I knew my dad was going to make me take it,” she says laughing, “because there were no other jobs!” She begrudgingly accepted the offer and says the hiring manager proceeded to send her to Houma, Louisiana – “not a female friendly place” – in what she describes as a trial by fire.

“There were two factors – they didn’t really want me and I didn’t want them!” Harris says, recalling a “terrible” first year where she went home every weekend. [Suddenly, the sound of a dog barking in the background gets louder. “You’re going to have to be quiet, Muffin,” Harris admonishes. These days, interviews always have some sort of surprise interlude, so I promise Muffin we will include her in the story and the barking recedes.] After that first year, Harris says she decided she was either going to pursue engineering wholeheartedly and give it her best and, if not, she needed to leave the industry and “go teach science somewhere.”

“There were two factors – they didn’t really want me and I didn’t want them!” Harris says, recalling a “terrible” first year where she went home every weekend. [Suddenly, the sound of a dog barking in the background gets louder. “You’re going to have to be quiet, Muffin,” Harris admonishes. These days, interviews always have some sort of surprise interlude, so I promise Muffin we will include her in the story and the barking recedes.] After that first year, Harris says she decided she was either going to pursue engineering wholeheartedly and give it her best and, if not, she needed to leave the industry and “go teach science somewhere.”

The first year, she had been given a C on her job performance review. “That’s never happened again. I said, ‘You will not be average. You will work hard and you will rise above.’ I have never been the best engineer, meaning the smartest – I’m a solutions-driven person – but I’ve always been able to pride myself on the fact that I am one of the hardest working.”

“It’s mind over matter and I tell kids, teenagers – especially mine – attitude equals altitude, period. Once I got my attitude straight and decided I was going to keep the job and make the best of it, I haven’t looked back.”

That didn’t necessarily improve the culture in which she was immersed, though. Harris says when she first became an engineer, she wanted to fit in and be one of the guys. She points out, “This is pre-Anita Hill, so everybody could say whatever the heck they wanted to say; everybody selling any kind of tool had a picture of a lady in a bikini and the pictures were all over the offices.”

It certainly didn’t get any better when she went offshore where, even now, 30 years later, women make up a mere 3.6 percent of the workforce. “I started off being very intimidated. I’d say, ‘Don’t make a big deal out of it,’ but it was always, ‘Woman onboard, woman onboard!’ There would be anywhere from 100 to 500 people on those rigs and 99.9 percent of the time I was the only female and the only African American.”

After proving herself offshore for seven years, Harris says, “I was widely respected.” If someone told her they didn’t have accommodations for a woman – in an attempt to get a male replacement – she would tell them, “I can go out there and do a great job or you can wait two weeks for someone else.” Laughing, she says, “I became known throughout the Gulf!” On a more serious note, she says, “You watch yourself evolve from this timid young person,” and that’s when she knew it was time to start looking for her next role.

After proving herself offshore for seven years, Harris says, “I was widely respected.” If someone told her they didn’t have accommodations for a woman – in an attempt to get a male replacement – she would tell them, “I can go out there and do a great job or you can wait two weeks for someone else.” Laughing, she says, “I became known throughout the Gulf!” On a more serious note, she says, “You watch yourself evolve from this timid young person,” and that’s when she knew it was time to start looking for her next role.

Looking back on it, Harris cites those long hard years offshore – “breaking that ceiling” – as one of two seminal moments in her career when she felt like she had “made it.” The second was being invited, as a young engineer, to present at the prestigious Offshore Technology Conference (OTC). Her mom ran out and bought her a “wow” business suit and she found herself in a room “with every big name at Schlumberger – the CEO, CFO, CIO” – strategizing with the investor relations team. “I’m sitting there with these names I have read about, thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m with the Schlumberger gods, and I’m being heard; I’m getting to talk.” The presentation was a success and she received notes of praise from those leaders regarding her performance. “And then it was back to the real world,” she says laughing.

Harris always made it a point to drop in on the Schlumberger offices wherever she was even when she was traveling with girlfriends on her days off. She would casually walk in and tell the secretary, “I’m a field engineer and I work in the Gulf of Mexico. Is there anyone around I can meet?” It was a tactic that paid off and led to a position in sales. It wasn’t the first time she heard that she landed the role because she was a woman or because she was Black, which she quickly countered with, “I got it because I spent my seven days off with the sales team, forming relationships with clients!” She discovered she loved sales and what it entailed – learning to play golf, entertaining clients, and visiting every continent except Antarctica – eventually becoming a global sales trainer.

“I spent a couple of years traveling the world and I think that is when I finally said, ‘Pinch me; I can’t believe I’m here.’”

As she neared the end of her 30s – “When you make big decisions, right?” – Harris got married and had a baby. As much as she wanted to “slow down for a minute and enjoy this baby,” she also made it known that she very much wanted to be part of a big management training group that worked on special projects around the globe. She lobbied for it – railing that leadership was trying to keep her off the project because she was a new mother – until she finally got it, only to discover that she would be expected to spend six weeks training in Perth.

“I said, ‘No, no, no. I don’t want to do that part of it, I’ve already done the international travel. I just want to learn project management.” Leaving her eight-month-old baby with her mother-in-law in Chicago, she traveled to Australia, where she was “horribly miserable” being separated from her daughter. “Be careful what you wish for,” she cautions, “and make sure that you aren’t going against what God has for you.”

Harris learned a valuable lesson from that experience and, when she had to spend six weeks in Venezuela to finish the training, she said, “I’m taking the baby with me.” When her mom pleaded with her not to [imitates wailing], ‘No, please don’t take the baby, you don’t have support, you don’t even speak Spanish!’ – she enlisted the help of a village. “Every week, someone new – college girlfriends, my sister, my parents, my husband, neighbors – came over to stay a week and watch the baby.”

Looking back on the reticence of leadership to appoint her to the project, Harris says thoughtfully, “We’re very quick sometimes to say, ‘That was racist and that was sexist,’ but everything isn’t racist and sexist; some things just aren’t for you. It definitely helped my career but, at the same time, if I had to do that over again, I would not have forced it. It wasn’t the time or the place.”

With the help of her husband, Dwayne Harris, a former captain in the military, whom she credits with giving her the “opportunity to have such a great daughter,” – Madison Harris, now 20 and a junior majoring in computer science major at Spelman College – Harris rose through the ranks at Schlumberger, culminating with her role as global director, which she calls her “dream job.” Building on her volunteer work with children, her children’s and young adult books, and her previous work recruiting college students, Harris says, “It was very impactful, very much who I am.”

“Environment, sustainability, governance (ESG) and the energy transition are so important. I spent a lot of time at student conferences on energy or the World Petroleum Council Youth Forum and really hearing tomorrow’s view, the European view, Asia’s view, on what we want our world to look like in the next 10, 20, 50 years based on how energy is going to continue to make an impact and how we want that energy to look through the transition.”

Harris calls taking a class on global sustainability at Cambridge University in January 2020 “eye opening.” She says, “The world would not exist as it is without the energy industry,” and believes some of the criticism leveled at the industry – oil and gas in particular – is unwarranted. However, she cautions, “We do have to be aware of the fact that our earth has finite resources; we don’t get a second chance.”

She stresses that it should not be an “us versus them” mentality. “We have to work and use our same resources, our same technology, and our same brilliant people to push [the transition] a little faster. We’ve done it before; we can do it again. Fighting with [other] people who are interested in making sure the earth is here for generations is not the direction we want to go.”

When she wasn’t increasing her knowledge of sustainability, Harris was preparing herself for a seat on the board of a publicly traded company, something she sees as the next phase in a woman’s career once she has reached the C-suite or a director position and had an impact at that level. Even before retirement, she had started putting together a board-ready portfolio and was recently accepted into the Greater Houston Women’s Chamber of Commerce “Women on Boards” preparedness program.

“That’s how these things work – happenstance and strategy. I think if I would have been more strategic and thought about one day retiring and serving on corporate boards, there may be something I would have done differently, but I wasn’t thinking that far out. My new advice to women, as they are working their career, is to look at what skill sets and what relationships you need to develop. Go ahead and think all the way through your ascension in your company and your ascension to being appointed to a public board. Have a strategy and a plan.”

Harris is well aware that unconscious bias is one of the reasons women’s representation is so low – making up only 14 percent of the boards of oil and gas companies in 2019, according to S&P Global – despite the fact that it has been proven that companies with more diverse boards have better return on investment (ROI). It is very much about relationships and board members tend to nominate prospective members who look like them and have similar backgrounds and experiences. And, until women make greater inroads, that is predominantly older, white males.

“It’s going to be an even harder ceiling to break,” muses Harris. But does anyone doubt she can do it? Not if they recall the prescient words of the men she worked with offshore long ago: woman on board, woman on board!

Headline photo courtesy of Niles Dillard

Paula McCann Harris’ Next Act

Paula McCann Harris’ Next Act

- The first thing I wanted to do when I retired was . . . travel for fun, which has not happened yet because of COVID-19, but I want to take a long European trip with NO meetings or presentations scheduled.

- My greatest indulgence has been . . . spending time down on our family ranch in Egypt, Texas. And also building my wine cellar and drinking delicious wines on WEEKNIGHTS!

- Something I didn’t have time to do while I was working but couldn’t wait to do was . . . piddle around shops, play tennis, lunch with friends, and wear workout clothes all day.

- Something I never want to do again is . . . wear suits every day.

- The first book I read for pleasure was . . . Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow.

- I have binge watched . . . Schitt’s Creek.

- As soon as it’s safe to travel by plane, train, automobile or however I can get there, I plan to . . . take a leisurely train ride through Europe.

- When I told my husband I was going to retire, his reaction was . . . he did not believe I would do it!

When I Grow Up, I Want to be an Engineer

When I Grow Up, I Want to be an Engineer

By Paula McCann Harris

When I grow up,

I want to be an engineer.

I want to make things and

make things BETTER, my dear.

I could make a NEW cell phone

or design a better house

I could design new DVDs

or better ways to catch a mouse.

I will CONSTRUCT

buildings and streets

and clean air products.

I can MAKE toys, and games,

and videos and trucks.

When I become an ENGINEER,

there’s so much I can do.

I need good grades in math and science. THAT’S TRUE.

There is a need for more ENGINEERS;

there are just too few.

I will make a difference

and make the world better for ME AND YOU!

Supported by Schlumberger ©2006. All rights served. Reprinted by permission. Available from Amazon.

Rebecca Ponton is the editor in chief at U.S. Energy Media and author of Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. She is the publisher of Books & Recovery digital magazine.