Technological advances have been a theme in the energy sector through the decades, used by aggressive operators to make drilling or production activities more efficient and cost effective. Recently, many of these technological advances have involved horizontal drilling or completion techniques in unconventional reservoirs.

One of the more intriguing and unconventional technological developments now being adopted is the use of drones, otherwise known as UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles), to assist the operator in oil and gas drilling, development, and operational activities.

Drones have been used in the industry for surveying, equipment inspection, spill documentation, emission monitoring, and to record surface damages caused by developmental activity. Several state regulatory agencies have used drones to inspect producing properties, to check on ice dams during the winter in streams near producing wells, and to try to locate abandoned wellheads.

With the focus on oil and gas activity we decided to test out our newly acquired drone to analyze its capabilities. The number of oil and gas projects we could participate in were limited since we were not an oil and gas operator. We considered partnering with a state oil and gas regulator, but timing and personnel issues made such a test program unfeasible.

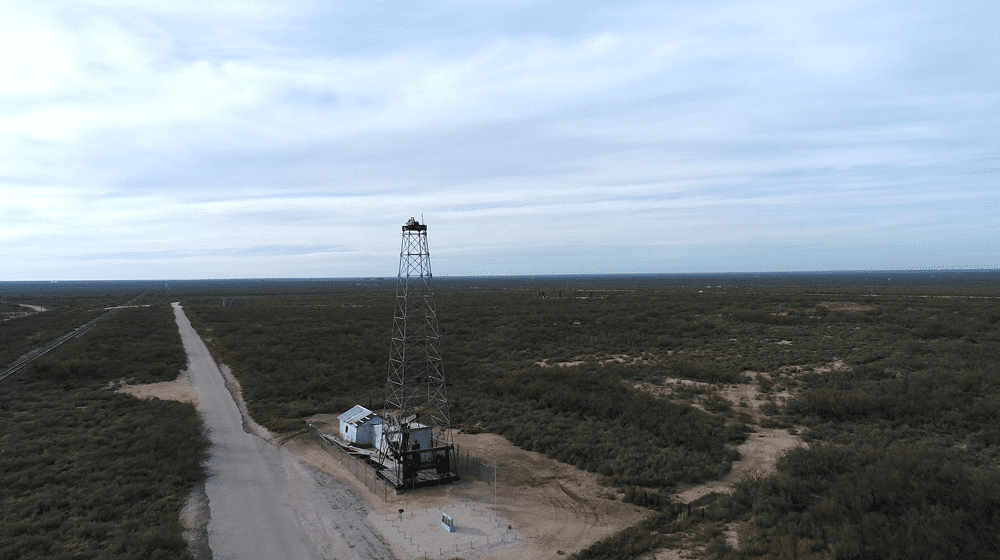

As an alternate, to test our drone capability, we proposed to use a UAV to film the Santa Rita #1 wellsite. This location is a historical site that has been preserved and is situated well away from civilization. Should we have operational issues, we reasoned, a problem experienced at the remote site would likely minimize the damage inflicted, as compared to say, a test flight and video in the Barnett Shale over well to do residential neighborhoods in Fort Worth.

Located in rural West Texas, an hour or so from Midland, the remote Santa Rita #1 well location is the discovery well of the Permian basin. Drilled in 1923 to a depth of 3,050 feet, the well “blew in” at 100 barrels per day. Unfortunately, due to its remote location, very few investors back in the day were interested in developing the field even after the discovery well proved successful.

The drone we purchased was one that is commonly used in the industry and sold commercially, costing around $1,500. It has a top speed of roughly 50 mph and can climb to roughly 20,000 feet, an altitude above which many smaller planes can safely attain.

Used by hobbyists, no license is necessary to fly a drone. But ours was an educational venture, not a hobbyist outing. We realized we would need a FAA drone operator’s license for the flight and filming.

UAV licenses are awarded based on a knowledge based test administered by the FAA. The applicant has to be at least 16 years of age and fluent in English. The license applicant must also pass a TSA screening test. We passed our FAA exam two weeks before filming.

Under FAA regulations filming can only be done during the day. The drone is limited to a maximum height of 400 feet. Some areas have been designated as restricted airspace, limiting drone operations. The FAA can grant exceptions to these regulations, but we felt we could successfully record and film under these conditions without requesting an exception.

In addition to federal regulations, state regulations also apply. In Texas there is an exception allowing for filming if it is being done for educational purposes. We were also flying over public lands and a public right-of-way. So we were not, in this situation, restricted by State of Texas regulations in the filming process. If we were not an educational venture the ability to film, and the required approvals, might have been more complicated.

We shot our video using a Garmin 360 camera mounted on the bottom of our drone. Due to the brisk wind, and the weight of the camera, the drone was initially somewhat unstable and wobbled a bit, but we were able to control that problem.

Once we had the filming complete, we took the video back to the University of Oklahoma, edited the two hours of film, and prepared a 15 minute virtual reality tape that students can view in The University of Oklahoma College of Law library.

A sixteen hour road round trip to the Santa Rita #1 is no longer necessary to explore the discovery well of one of the largest oilfields on earth – if not the largest. The student can experience the narrated Permian Basin expedition in a custom, air conditioned, seat in front of a computer screen 425 miles away from the well.

Technology continues to create niches in the energy sector, both from an operational and educational standpoint. Over the longer term

we are all better for it.

Photos courtesy of Professor Kenton Brice and Joseph Dancy -OU College of Law

Joseph R. Dancy is Executive Director of the University of Oklahoma College of Law’s Oil & Gas, Natural Resource, and Energy Center. He regularly speaks to professional groups on pressing energy issues and teaches Energy Law and Finance.