Oil is a closely watched commodity, and when its price moves, whole industries and whole economies can be shaped and defined. With the price of oil’s decline in December 2015 to below $35 per barrel for the first time since 2009, the U.S. oil exploration and production (E&P) sector has slowed to a blip of its previous boom. The price of oil is so critical to the operation of E&P companies that some of the largest ones in the U.S. south declined to go on record about the resources they watch and use to create forecasts and make profitable business decisions moving forward. So, what is behind the all-important price of oil and what’s the current thinking on how to anticipate its next move? Oilman spoke with two professors at the University of Texas at Austin McCombs School of Business to find out.

Market Status at Year-End 2015

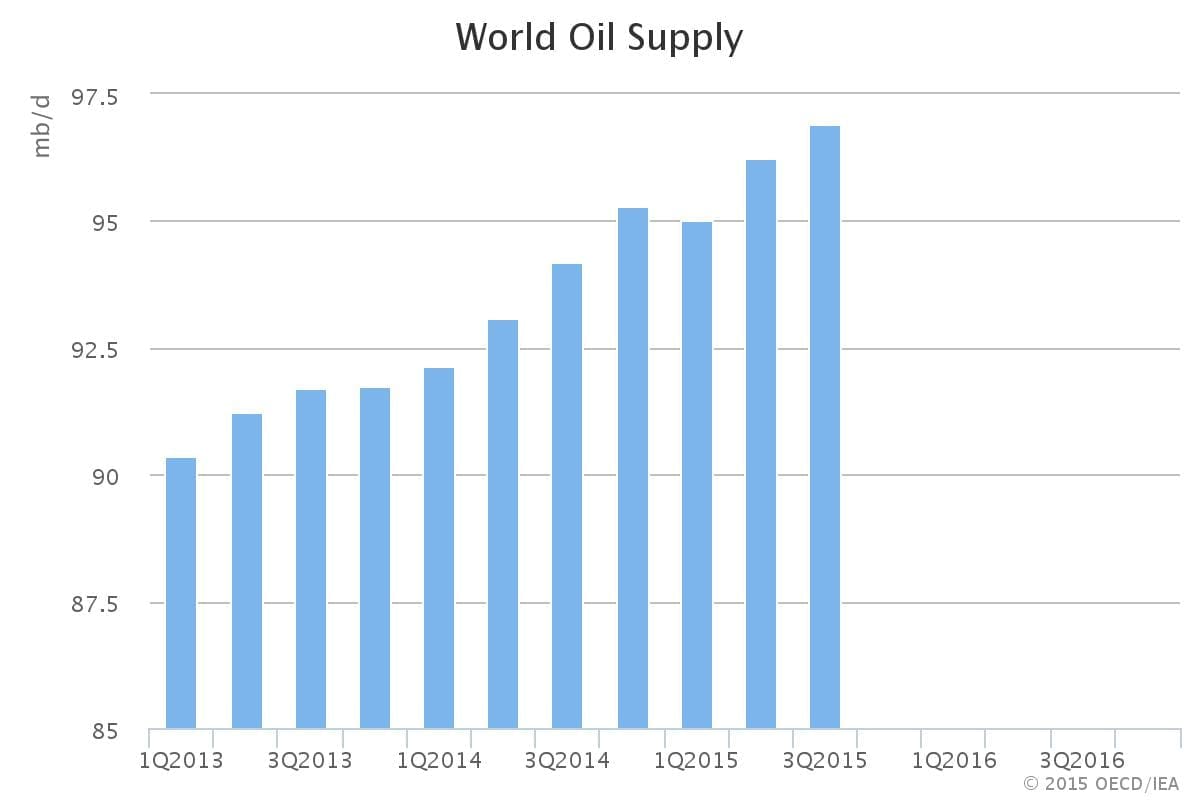

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) December 2015 Oil Market Report, OPEC’s decision to scrap its official production ceiling and keep oil flowing is a de facto acknowledgment of current oil market reality. IEA said that the exporter group has effectively been pumping at will since Saudi Arabia convinced fellow members a year ago to refrain from supply cuts and defend market share against the ongoing rise in non-OPEC supply.

IEA’s World Energy Outlook for 2015 points to one scenario in which oil prices remain low for an extended period, with a new market equilibrium emerging at prices in a $50/bbl to $60/bbl range that lasts well into the 2020s before climbing to $85/bbl in 2040. That scenario makes certain market assumptions, including sluggish near-term economic growth; a stable Middle East in which key producers look to increase their share of the market; and resilient performance from key non-OPEC producers, particularly U.S. tight oil.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) in its Dec. 8 Short-Term Energy Outlook estimated that total U.S. crude oil production declined by about 60,000 b/d in November compared with October. Crude oil production is forecast to decrease through 3Q16 before growth resumes late in 2016. In addition, projected U.S. crude oil production averages 9.3 million b/d in 2015 and 8.8 million b/d in 2016.

EIA forecasts that Brent crude oil prices will average $53/b in 2015 and $56/b in 2016. Forecast West Texas Intermediate crude oil prices average $4/b lower than the Brent price in 2015 and $5/b lower in 2016.

Forecasting

The cost per barrel of oil is determined though a myriad of decisions that influence the supply of oil and its demand. Forecasting the price of oil, therefore, has traditionally been reliant on predicting those decisions. Because companies that find trustworthy forecasting models can move through boom and bust cycles with vision, researchers continue to seek out ways to improve on current methodologies.

About three years ago, professors James Dyer and Joe Hahn of the McCombs School of Business developed a new tool that uses information about the value of assets in financial markets to estimate the fundamentals of oil supply and demand and the resulting price. Their study, which was originally published in Energy Economics in 2014, analyzes 23 years of historical oil futures prices to model and forecast prices.

The study was part of a program of study that Hahn originally began working on for his dissertation and that he has continued to work on as part of a larger project on energy prices. One of the main inputs to the models that Hahn was creating was a forecast of commodity prices, and oil was one of those commodities.

Hahn and Dyer focused on creating a model that allowed them to develop forecasts that diverted from traditional subjective thinking present in models based on supply and demand.

“We’ve been interested in models that will allow us to come up with forecasts that are in some sense objective,” Dyer said.

Models based on supply and demand, Dyer said, tend to be more complex models that try to collect information about various indicators of activities in terms of the production and consumption of a commodity, such as oil or natural gas, and the balance between the rates of the production and the rates of use of those commodities. Those models then require some assumptions about how prices might react to the changes in supply and demand, he said.

One of the challenges of those models, he added, is that the people who build the models make assumptions that reflect their different views or opinions and different estimates of the relative impact of changes in oil and gas prices as supplies and demands change.

“Some of that change can be estimated from market information, but in other cases, there is relatively more subjectivity in those types of models than in the type of model that we have been developing,” Dyer said.

The model developed by Hahn and Dyer relies more on information that is available in the marketplace and can be reproduced by other people using the same techniques. Their model, Hahn said, is based on “the wisdom of the crowd, in that we look at what the market is trading in terms of futures data for oil.”

The people trading in those markets are running their own proprietary fundamental/economic models, and they are placing bets on whether the price is going to go up or down or what level the price is going to be at in the future.

“That’s all impounded in market data through futures prices,” he said. “We use that data from the market – and the composite of everyone’s individual expectations that impounds itself in futures prices – to calibrate our model. So we’re not putting any of our own subjective judgments in the model.”

The forecast that results from the objective model also provides bounds, Hahn said, explaining that whatever the expected value is in any given forecast, it is likely to be wrong.

“What our forecast tries to provide is that expectation with an error bound around what that expectation is over time,” he said. “So if you look at where prices have fallen to today, it would be close to the lower bound of that forecast.”

Hahn noted that most fundamental forecasts missed the fact that OPEC would adopt the supply policy that has resulted in the current supply glut.

“That’s not something that was picked up in most models and couldn’t have been picked up in a market-based model if the market participants weren’t anticipating it,” he said.

Because there are any number of unforeseeable factors that can come forward and influence the price of oil, Hahn said it is critical to update the objective model as that information shows up in the market.

Although Hahn and Dyer have not updated the model since the study was published in 2014, they said an addendum to the study with an update would be timely.

For now, they are working on a similar forecasting model for natural gas.

“We’re building some models that relate to the cost of electricity, and a forecast of the cost of natural gas will be an important part of those models,” Dyer said. “We expect to have those models available on a public website for use or manipulation by the public ideally within the next six months”

Dyer and Hahn plan to update the cost-of-electricity models on a regular basis so that they can be run with current forecast estimates that are based on changes in the market information regarding futures prices. The website, Dyer said, would be provided by the Energy Institute on the University of Texas campus.