Blow outs are typically associated with the perils of drilling, but these days there is a looming threat to existing production. Decades of downspacing in many U.S. basins have resulted in a large-scale problem for the industry where blow outs, water outs, and other adverse, sometimes catastrophic events can and do happen to offset wells during hydraulic fracturing. The extreme pressure generated from pumping thousands of gallons of fluid into a wellbore can have unintended consequences in the form of a fracture hit, or frac hit, that forces fluids, gas, and water upward in wells thousands of feet away. Frac hits are a double-edged sword. Operators sometimes report improved production after a hit. Either way, a frac hit is an uncontrolled well event that the North American oil and gas industry increasingly struggles with.

From drilling and completion to production and field operations, the oil and gas business is laser focused on controlling equipment and processes in order to protect people, the environment, and capital investments, which is why the uncontrolled and unpredictable nature of frac hits is so problematic. The role and importance of hydraulic fracturing is indisputable, perhaps the single most critical process that triggered the Shale Revolution and emergence of U.S. energy dominance. At the same time, fracking injects unwanted uncertainty and interference with neighboring wells.

It’s all about location, location, location as realtors often say. The frac hit crisis has its epicenter in the Permian Basin with the problem spreading to the Eagle Ford and beyond. The shale reservoirs of these regions that make fracking so effective also make frac hits more likely to occur. Spacing in the Delaware Basin or Lower Eagle Ford has become increasingly tight, with some laterals packed within the length of a football field. These tightly spaced laterals that make fracking so effective can stack or horizontally position wellbores very close together. This combination of geology, spacing, and stacking are a perfect recipe for well interference.

On the production side, frac hits can at worst blow out and wreck long-term production efficacy, and at best stimulate and increase production in rare cases. It’s a gamble as to what will happen, which is why operators often choose to shut-in their wells to avoid damage from a frac hit. Frac hits also pose similar risks during other phases of the well life cycle, including drilling, completion, drill-out, and flowback.

In the U.S. shale plays, where close well spacing and stacking are common, there is a very real crisis brewing. With ever decreasing surface spacing and increasing lateral lengths, the situation is starting to resemble a pressure cooker. At a macro level, though, the threat of frac hits is partly a function of state and local regulation. Texas tends to be very flexible with surface permitting, allowing for the closely packed wells that simultaneously make the state the dominant North American producer while creating massive potential for well interference. In contrast, Colorado’s DJ and Niobrara Basins are relatively unaffected by frac hits due to the strict regulations imposed on well spacing. However, the pervasive frac hit crisis is already spreading beyond Texas with North Dakota’s Bakken joining the Permian and Eagle Ford as frac hit hot spots.

The economic impact of frac hits is twofold. First, operators impacted by a frac hit must contend with damage to wellhead, wellbore, and pay zones. In severe cases, that might require a complete workover or recompletion, costing an operator millions. Secondly, mitigating the impact of frac hits by shutting-in a well has an immediate impact on a producer’s bottom line. Today’s multi-stage frac jobs can take days or longer to complete, in which time production and sales are shut in. Given the continued momentum of drilling, the cumulative economic impact of frac hit damage and shut-in production is staggering.

If shutting in a well is the solution to protect producing offsets during a frac job, knowing when to shut in is critical. Even 5 years ago, there was little warning for producers. Even staying diligent about consistently monitoring permits and publicly reported completion dates, pumpers who spot a rig going up near your property may have been your only defense. Even with public data at your fingertips, permits and completion dates are always subject to constant change. The situation was reactive, requiring producers to pick up a phone and reach out to their peers in order to coordinate shut-ins around a frac schedule.

Transitioning to a more proactive approach, a small number of Permian operators created an informal coalition with the goal of sharing their frac schedules and mitigating the economic impact of interwell pressure communication. Members of the coalition approached the problem in different ways, with many in the Delaware sub-basin relying on e-mail to exchange spreadsheets containing location and dates of planned hydraulic fracturing. This information was manually collated and loaded into GIS applications to determine whether or not a frac job would impact a producer’s acreage. This decentralized approach was time-consuming, lacked standards, and was prone to human error.

In contrast, Permian frac hit coalition members in the Midland sub-basin and took a more centralized approach by setting up a dedicated FTP server. Completion schedules were uploaded to this server where spreadsheets could be bulk downloaded. However, the Midland group encountered many of the same challenges as the Delaware group, including lack of consistency, multiple document versions, and limited governance. Location of the FTP server also switched from one producer to another, making it uncertain as to who would own and operate the required infrastructure in the long-term.

Recognizing the need for a more structured, transparent, and scalable solution to sharing frac schedules, one of the largest operators in the Permian Basin set out to develop an internal software application to enable coalition participants to key in their planned completion activities rather than relying on spreadsheets. The application would provide a number of benefits, including the ability to store frac schedule data in a database for rapid reporting. It would also allow participating operators to access frac schedules remotely with a web browser.

As the well interference problem spread across the Permian Basin, more and more operators needed to coordinate hydraulic fracturing operations. The problem was too big for the operator developing the well interference application, who realized the company would face mounting complexities for administration and upkeep of software that would potentially serve hundreds of producers. Questions about the sustainability and stewardship of the envisioned well interference application led the coalition to find a permanent solution that would open up the benefits to the entire Permian Basin. The answer to a long-term solution for mitigating the impact of Permian frac hits would leverage a reciprocal well data sharing service already used by many of the coalition producers. Operated by PDS Energy Information, the Well Data Exchange is widely used across the oil and gas industry to seamlessly share structured and unstructured drilling, completion and production information between operators and their partners. Recognizing that the PDS Well Data Exchange offered the reach, security, and commercial-grade infrastructure needed to manage the large-scale frac hit problem, the coalition approached PDS who took over operation and development of the well interference application.

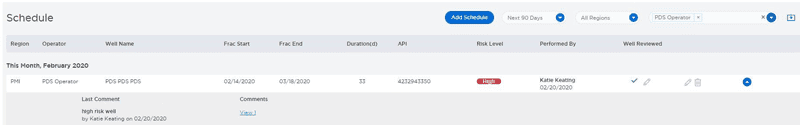

PDS deployed the application on its existing Well Data Exchange network and continued to develop enhancements and functionality. Called the FracX (Frac Interference Exchange), the new data exchange is provided as a no-cost service to the oil and gas industry by PDS. Building on the initial vision of the Permian coalition, FracX includes granular access control and new automation features that enable completion data to be seamlessly exchanged between participating operators. Importantly, frac schedules that are manually loaded or automatically imported into FracX are normalized, providing a standard dataset that accelerates the sharing and coordination of completion activities between companies.

Today, the PDS operated Frac Interference Exchange is used by every major Permian producer. The explosive growth in operator adoption reflects the urgency in the region to proactively track potential frac hits with similar adoption being seen in the Eagle Ford/Austin Chalk along with interest in the Bakken and Haynesville.

FracX users can contribute their completion schedules to the exchange either by uploading a spreadsheet using a web browser or by automatically exporting planned well locations and completion dates from their GIS system. This data is then automatically synchronized with the exchange by FTP or API data transfer. On the receiving side, producers can view completion information in a web browser, which provides a map-based interface for quick look analysis. This information can also be automatically downloaded and imported into an operator’s GIS system where potential well interference can be visualized and precisely tracked.

By accelerating collaboration and elevating confidence in data, FracX helps oil and gas companies in a number of important ways that minimize the impact of frac hits. Operators who submit their completion schedules contribute to the common benefit of all producers and can proactively work with nearby offset producers even if those producers are not yet on the exchange or have not yet contacted them for a variety of reasons, including change of ownership. FracX helps producers better understand whether or not a shut-in is required. If a shut-in is required, the system facilitates coordination between the producer planning a frac operation and all nearby producers so that the window of time when production is offline is kept to a minimum.

Collaboration is the ultimate answer to the pervasive frac hit crisis, which may just be getting started. The initial instinct of the Permian frac hit coalition to pick up a phone and work through a solution was the right one. Innovation has been the game-changing component that accelerates that collaboration so producers can finally get ahead of the frac hit problem on a large scale.

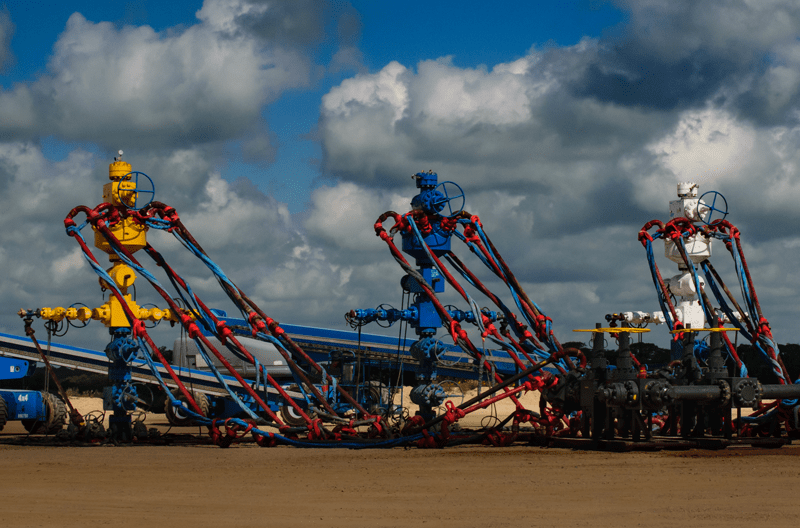

Headline photo courtesy of PDS Energy Information

Barry Barksdale founded PDS in 1990 and continues to serve as President. From 1996 to 2008, Mr. Barksdale served as a consultant and expert on numerous royalty cases where the PDS Posted Price Database was the de facto standard database for such litigation. Prior to founding PDS, Mr. Barksdale had a variety of roles around crude gathering and gas gathering systems. He attended the University of Texas at Austin and continues to hold out hope for the return of their football program.