With growing worldwide momentum in decarbonization, the oil and gas industry is starting to acknowledge its impact on climate change, and is now increasingly committing to carbon neutrality goals and taking part in collaborative decarbonization initiatives. The majority of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with the oil and gas industry are Scope 3 in nature, i.e. emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels. Oil and gas majors are taking steps to eliminate their Scope 3 emissions, but this is a long-term and complex endeavor; tackling Scope 1 emissions is easier as they are within the direct control of oil and gas companies.

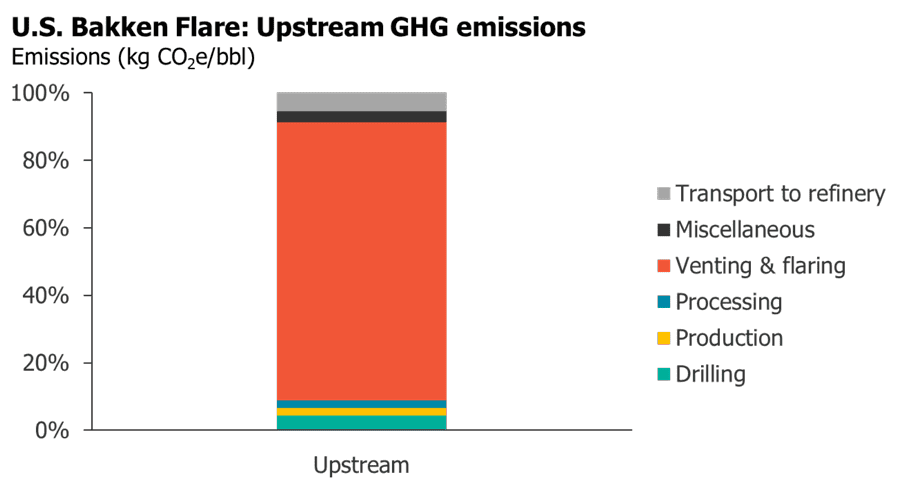

The majority of Scope 1 emissions for the oil and gas industry comes from flaring of associated gas, a form of natural gas that is frequently produced as a byproduct in oil production. Due to a variety of safety, economic and convenience factors, it is common practice in the oil and gas industry to burn associated gas via flaring or vent it directly into the atmosphere. The flaring of associated gas represents a growing source of GHG emissions for the sector, particularly in regions like the U.S. that have experienced rapid development in recent decades. While flaring volumes and rates vary significantly depending on the reservoir and its characteristics, flaring emissions can make up a significant portion of upstream GHG emissions. In the U.S. Bakken oilfield, for example, venting, flaring and fugitive methane emissions contribute nearly 90 percent of the field’s upstream GHG emissions due to its moderate gas content and high flare rates.

Flare reduction goals have been at the forefront of decarbonization with growing commitments from both industry players and government entities to eliminate flaring altogether by 2030. In order to meet these flare reduction goals, particularly in regions without direct access to gas markets, operators must find a productive use for the associated gas.

There are several existing options for oil and gas operators to reduce flaring at new and existing facilities. The simplest and most optimal solution is to leverage gas pipeline infrastructure to capture, gather and transport associated gas to local gas markets, but this is not always a feasible or economical option for all assets. In remote offshore facilities, for example, the high capital expense of building new pipelines may not be justified for the volume of associated gas that could be sold to onshore markets.

Another practical solution is to use associated gas to power operations on-site. One emerging idea from Crusoe Energy Systems involves the use of associated gas to power modular onsite data centers for digital operations like bitcoin mining. This is a unique approach to flare mitigation that enables operators to make a profit on produced gas in areas with limited takeaway capacity, but would not be feasible for most offshore assets due to its large footprint.

One way to overcome the lack of gas pipeline infrastructure is to simply leverage oil pipelines instead. Doing so requires the conversion of associated gas to a liquid form, which can be done through Fischer-Tropsch technology, in a process known as gas-to-liquids (GTL). Fischer-Tropsch technology is proven at the commercial scale in Malaysia and Qatar but it has only been deployed for large-scale operations. To date, there is no small-scale Fischer-Tropsch project that proved successful. The economic viability of GTL projects is dependent on the price differential of natural gas and crude oil; in periods of low natural gas price and high oil prices, GTL projects can be economically viable. The world witnessed such a situation in the early 2010s when oil prices were over $100/barrel. At that time, multiple companies offering small-scale Fischer-Tropsch solutions popped up and targeted associated gas streams; however, oil prices crashed in 2015 and destroyed the economic prospects of GTL projects using associated gas. The ongoing pandemic suggests that it is unlikely oil prices will reach their heyday of the past decade.

Despite the challenging economic situation caused by the crash in oil prices, small-scale Fisher-Trospch technology developers survived and have turned towards greener pastures – renewable fuels. Companies such as Fulcrum Bioenergy and Velocys are currently developing GTL projects converting solid municipal waste into renewable hydrocarbon fuels in the U.S. and U.K., respectively, leveraging the financial credits available for low-carbon fuels in those countries. Over the past few years, Fischer-Tropsch technology has found yet another use-case – CO2 utilization. In this area, CO2 and hydrogen (presumably obtained from water electrolysis) are converted into liquid hydrocarbon fuels via a series of processes including Fischer-Tropsch. The application of Fischer-Tropsch in CO2 utilization has so far only been tested at the demonstration scale, but the first commercial-scale project will be built in 2026 by Norsk e-Fuel in Norway.

Producing hydrocarbon fuels from CO2 is counterintuitive as the CO2 itself originally came from fossil fuels. Norsk e-Fuel is essentially building a plant that is based on reversing the combustion process. Despite its challenging economics, the process is necessary for the energy transition. Unlike the road transportation sector which can be decarbonized with electricity, the aviation and marine sectors will still rely on hydrocarbon fuels due to its unparalleled energy density compared to batteries. If we cannot change the type of fuel we use, then we need to change its source – in this case, swapping crude oil with CO2 and green hydrogen.

Fischer-Tropsch technology offers a unique opportunity for oil and gas companies looking to succeed in the transition to a low-carbon economy. Synthetic fuels made from CO2 are indispensable for the industry to neutralize its Scope 3 emissions; however, the market for CO2-based fuels is still immature. But Fischer-Tropsch technology can also be used in the more pressing case of eliminating the industry’s Scope 1 emissions through abatement of flaring. Admittedly, producing synthetic fuels from associated gas merely offsets Scope 1 emissions to Scope 3 emissions, but deploying Fischer-Tropsch technology today will provide the oil and gas industry with valuable expertise and know-how in anticipation of the technology’s much-broader deployment for CO2-based fuels. This means oil and gas companies should prioritize Fischer-Tropsch technology today in their quest for carbon neutrality.

Headline photo courtesy of Lux Research

Holly Havel is a research associate for the energy team at Lux, where she conducts research on technological developments and market trends in the oil and gas and power generation industries. Prior to joining Lux Research, Havel worked as a wellsite geologist on oil rigs in Oklahoma where she logged lithology, drilling parameters, gas units and formation tops for the duration of the well logging period. More recently, she has experience as a scientist for an environmental consulting company where she conducted field activities at active petroleum release sites and submitted regulatory reports to local and state agencies. Havel holds a B.S. in geology from Union College.