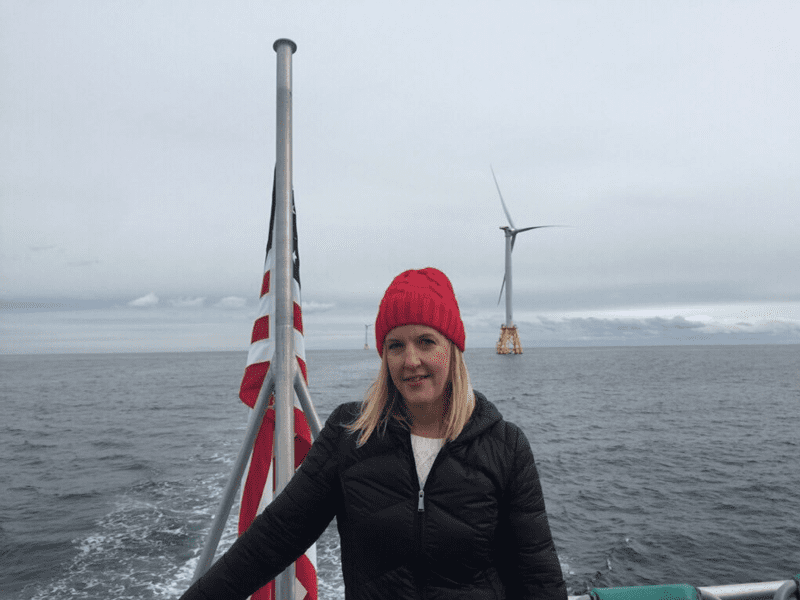

Abigail (Abby) Ross Hopper’s career has spanned the energy spectrum from wind to fossil fuels and now to solar, as president and CEO of the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), since January 2017. She talks to OILWOMAN about the current state of the solar industry as it deals with the COVID-19 pandemic and why she believes solar will help lead the energy transition.

Rebecca Ponton: You worked in wind energy when you were with Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley’s office and fossil fuels when you were the Director of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). You’ve got this wide breadth of experience in energy. How did you become involved in the solar industry?

Abby Ross Hopper: When I was leaving BOEM, I surveyed the energy landscape. I knew I wanted to continue to be involved in energy because it’s just such a fascinating area, and also at the intersection of policy and politics because that’s just a fun place to be. From my judgement, solar is going to be one of the key drivers of our energy transformation, and I think there’s some really broad consensus in our nation that we need to move to a cleaner energy system. Solar, offshore and land-based wind, are going to lead that transformation, so it made sense to me to be a part of one of the fastest growing, innovative energy sources in the world.

There is an entrepreneurial spirit in solar that sets it apart from other sectors I’ve worked in. It is an incredibly exciting industry. Part of that is because it serves different markets. There’s a sector of it that’s focused on residential; homeowners want to have more control over their own energy source. There are corporations that want to save money and have made commitments. There are utilities [whose] customers are demanding it and it’s the lowest cost option. So, there are all of these different segments and customer bases, and that means it’s really a dynamic industry.

RP: What role is solar going to play in the energy transition?

RP: What role is solar going to play in the energy transition?

AH: I think it’s going to lead the transition to a clean energy economy. If we look back over the last five years or so, solar was either the number one or number two source of new electricity generation. What’s actually being built now? What are investors investing in? Solar. That’s only going to increase. We do a five-year forecast that’s updated every quarter and – I have to say everything with an asterisk because of the impact COVID-19’s having right now – but directionally, our trajectory is up; we will continue to grow for the foreseeable future.

RP: What do you feel like is the biggest obstacle, then, to solar being more widespread?

AH: One is really around the disruptive nature of solar. If we think about the market rules and the utility construct that have been in place for a very long time, they were set up for large power plants that only distributed energy from the power plant to the consumer. Obviously, a lot of our distributed generation requires two-way flow. So, the system itself can be challenged, but also the market rules.

We have tons of big power plants that deliver from a large power plant to the customer, but the rules around access to the market, access to interconnection, and what we can bid on in the wholesale markets, were also written when solar didn’t really exist; they were written for fossil fuels. And so, we spend a lot of time in the regulatory space, making sure that the marketplace that we operate in is cognizant of our technology, and we can compete there. That’s one thing – evolving both the actual system – the business model – and the regulatory and policy framework, to reflect this new technology. And the second thing I would say is our prices. The price of solar has dropped so dramatically, about 70 percent.

It’s amazing. People often, understandably, have an outdated view that it’s an expensive source of energy, and that people go solar because they want to save the planet, but that you have to be wealthy and have disposable income to do it. That’s not the case anymore. We compete in requests for proposals (RFPs) that utilities put out, and we can beat the price for other generators. There’s a public education campaign [component] as well, so that consumers really know, not only are we saving carbon, and creating jobs and investments, we’re also saving money because we’re going to provide you affordable power.

RP: Would you say the biggest misperception about solar is price and affordability?

AH: I would. Also, I live in the world of politics. There is a misperception that solar is a Democratic [with] a big D – a Democratic Party issue. Two summers ago, we looked at where solar is built in the country by congressional district, and it was about half Republican, half Democratic districts. If you look at the top ten solar states for installations, some have Democratic governors, some Republican.

We’re in this big lobbying effort right now. We just had a letter supporting our request from Congress: 25 Democratic congressmen and 25 Republican. The state of North Carolina is the number two state for solar in the nation, which surprises some people. Thom Tillis, the Republican senator, knows how much investment solar brings to his state, and so he is very supportive. So, I would say that’s the other misperception; if folks aren’t following it, they assume that it’s just liberals that care about it.

RP: It’s a non-partisan energy.

AH: It is. I just had a conversation with Bill Cassidy, the Republican senator from Louisiana, whom I obviously talked to at my BOEM days, and we talked about solar because it is a really important part of a balanced energy portfolio.

RP: What do your lobbying efforts entail and what kind of reception do you get?

AH: Pre-COVID, we were on track to have a record-breaking year in terms of how much solar was built in the United States. We started 2020 with about 250,000 people employed in the solar industry in this country. We anticipated adding 50,000 more people this year [for a total of] 300,000 employees; instead, we lost 72,000 employees in four months.

People got laid off because of COVID. We are lobbying for some fixes to our tax credit to really allow us to be able to use it more effectively when the rest of the economy is crashing down around us.

RP: How is the solar industry weathering, no pun intended, the crisis? It may be a misperception to a certain extent, but I would think so much of the work occurs out in the field, installing panels. Can a lot of that work be done remotely? Is it digitized? How has the industry adapted?

AH: Our companies have evolved quickly to put the CDC guidelines into place. We can social distance and install safely. What’s harder to do is door-to-door sales, and going into people’s homes, if you’re doing it on the residential side, to inspect their electrical boxes. On our commercial side, we do a lot on schools, and hospitals, and universities and, especially at the beginning of COVID, they [didn’t] want anyone on their property, so there were some real issues with work stoppages. Not because we couldn’t put the panels in place safely, but because it was part of a more complex system.

Our company has moved quickly to online sales, to virtual meetings for the customers, to online permitting. Our products have to be inspected, and all of those inspectors are working from home, so we’ve made progress in making that more efficient.

What we’re seeing now, though, is that the tax credit, especially for the large-scale projects, is incumbent upon tax equity. Companies and banks that have a tax liability want to use the tax credit to offset that. Banks just had their worst Q2 since the Great Recession. So, the availability of that tax credit is shrinking dramatically, and that means they won’t be able to invest in our projects. So, part of what we’re asking Congress for is to make that tax credit refundable to developers themselves, instead of to tax equity partners, so that we can keep building. There is a causal effect because the economy is really struggling. It’s not that people don’t want to buy solar; it’s that the way in which solar is financed, is imperiled.

RP: The tax credits originally were, and maybe they still are, due to expire in 2021. If extending them is not part of the relief package, how is that going to impact the industry?

AH: It will slow the growth of our industry. Solar will continue to lead the transition to a clean energy economy, but we could do it much more quickly, and bring jobs, investment, and clean air to our nation with more support of a tax policy. [For example], if the residential side goes away, and the commercial side goes down to ten percent, our companies know and anticipate that [might happen] but, given that we have many intersecting crises in our nation at the moment, certainly helping solve the private crisis and the economic crisis by having a policy supportive of solar would be a wise investment for our nation.

RP: As we know, all energy fields, whether oil and gas or renewables, are male dominated. There are various initiatives but what can we do to make those industries more appealing, not just to women, but also other minorities?

AH: One of the most important things we can do is just recognize it as an issue. I run a business and I represent businesses. Understand why it makes sound economic sense for us to invest in diversity efforts. Companies with diverse leadership teams make more money, they access more markets, they get more customers, so those are really important business reasons.

Representation matters. Having women and people of color in leadership positions, on your boards, in your senior management, being the face of your company matters. I think having the leadership, someone other than women and people of color, also talk about these issues [is necessary]. The white male leadership saying, “This is a really critical priority for us, and we’re going to invest in it,” is one really important way we could change things.

It doesn’t just stop at the front door. It’s great to hire a diverse candidate, and have that person walk in on day one, but that’s just the beginning of the conversation. They need to feel included. It’s that cultural piece that is so critically important. As someone who runs a company, and someone who talks with people who run companies, I think a lot about the kind of cultures we’re creating in our workplaces. There needs to be intentionality around that.

We have really been challenged in our own organization, as the nation is reeling from the most recent murders of our fellow citizens, of dealing with justice. We talk about diversity; we talk about inclusion. We’re also talking about racial justice, and how do we bring that into the work that we’re doing? I think that they’re all incredibly important.

At SEIA, we created a board-level taskforce just [recently], to really dig deep, and figure out what we can we do. How do we get more women and more people of color into our organizations? What are the mentorship programs? What are the hiring practices? Where do we spend our money? How do we support black and women-owned businesses? How do we bring that into our policy? How do we make our own board more diverse? We’re rolling up our sleeves and getting really deep into action because that’s what it takes. It’s not going to work if we just have a diversity day one day a year, and then go back to business as usual.

Chapter 11

Abigail Ross Hopper, Director, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

Abigail Ross Hopper was named the first female director of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in 2015 and served in that capacity until 2017 when she became the first woman president and CEO of the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA).

Abigail Ross Hopper was named the first female director of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in 2015 and served in that capacity until 2017 when she became the first woman president and CEO of the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA).

Internally, there is an active diversity management program in the Department of the Interior (DOI) in which BOEM participates, but there is not a dedicated women’s network within the organization.

“It might sound funny,” Connie Gillette, deputy public affairs officer and media relations manager, says, “but we don’t have a need. It’s the most equitable place I’ve worked.”

Working in an organization that appreciates diversity doesn’t prevent Hopper from encountering gender bias outside of her own environment. “I see ways in which, as leader of this organization, I’m treated differently, perhaps, than leaders of some of my sister organizations that are men. I still have to speak up and make sure that I’m heard. It’s not uncommon that I will express something in a meeting and then a man will say the same thing and he will be heard.”

She cites another example. “I was somewhere; I can never remember where” – a reflection of the amount of travel her job entails – “and this man couldn’t believe that I actually headed BOEM.”

“He said, ‘No, which department are you in?’

“I said, ‘I’m head of it.’

“He said, ‘No, which section?’”

While Hopper says she has not encountered blatant sexism in her current job or her previous job with the Maryland Energy Administration (MEA), she says it is the immediate assumptions people make that she finds more problematic. “There are just more subtle ways that women have to pay attention to and address or they continue.”

“I pay attention to who people make eye contact with because you make eye contact with the person you want to influence. There are many meetings where people from the outside will meet with my deputy director, who is a man, and me, and will look only at and address him. I have been asked many times when the director is coming to the meeting and I have to tell people, ‘She’s already here.’”

Excerpted from Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil & Gas Industry (Modern History Press; May 2019) by Rebecca Ponton.

Rebecca Ponton is the editor in chief at U.S. Energy Media and author of Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. She is the publisher of Books & Recovery digital magazine.