As the global energy transition accelerates, the tools of diplomacy are evolving to match the complexity and urgency of this transformation. Traditional international agreements still matter, but they are often too slow and inflexible to address the fast pace of technological change, shifting markets, and urgent climate goals. In this setting, Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) have become more important than expected. Though usually seen as non-binding or preliminary, MOUs are increasingly used as practical frameworks for cooperation in energy projects and policies. This paper argues that MOUs have emerged as pivotal instruments in energy diplomacy, not merely as procedural agreements but as strategic frameworks that institutionalize regulatory alignment, de-risk investment, and embed sustainability mandates across borders.

To guide the analysis, the paper uses a three-part framework for evaluating how MOUs function in energy diplomacy. First, legal embeddedness, how they anchor agreements in existing legal systems or regulations. Second, institutional coordination, how MOUs structure cooperation between regulators, diplomats, and technical bodies. Third, investment signaling, how these agreements attract private capital and reduce project risk by clarifying timelines, responsibilities, and dispute resolution mechanisms. This structure will be applied to both case studies to show the diplomatic logic behind each element.

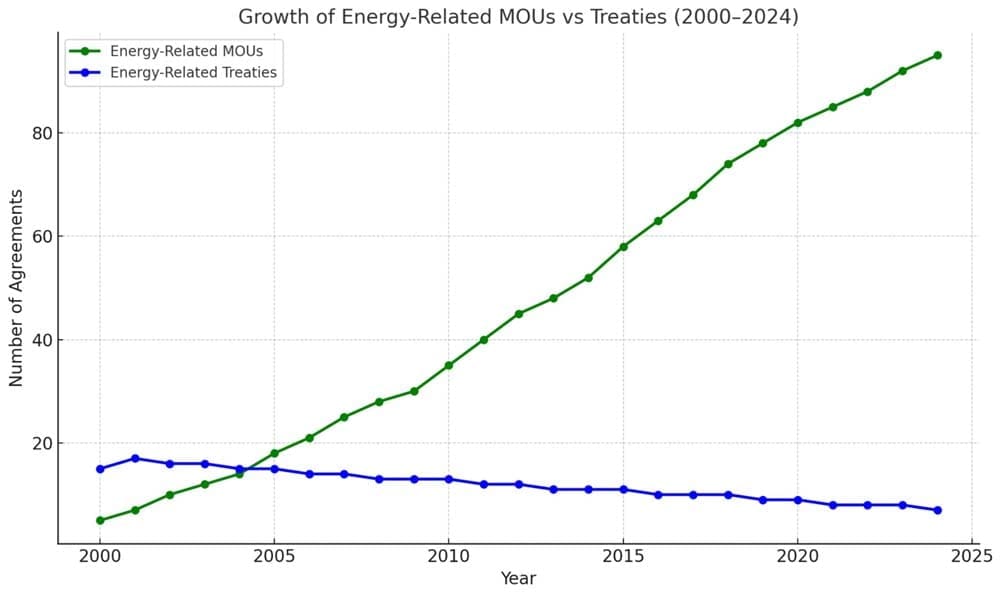

MOUs sit in a legally ambiguous space: They are not binding treaties and typically avoid formal ratification, yet they often carry real weight by shaping behavior, coordinating institutions, and guiding regulatory implementation. Yet in practice, MOUs are often embedded in legal frameworks and used as the basis for future regulatory action. Their main value is not legal force but their ability to set expectations, provide structure, and create a clear path for future cooperation.1 In energy diplomacy, this flexibility has become one of their greatest strengths. This is not a theoretical shift but an observable trend.

As Figure 1 shows, the number of energy-related MOUs has grown steadily since 2000, overtaking formal treaty use in the sector. This reflects a global move toward flexible, fast-moving frameworks capable of adapting to rapid technological and policy change. Additionally, the growing use of MOUs reflects a shift in how countries work together on energy. In the past, energy diplomacy focused mostly on oil and gas deals, which were driven by security concerns and state-to-state bargaining. Today, energy cooperation involves shared infrastructure, clean technology, investment from the private sector, and environmental goals. These issues are complex and constantly changing.2 MOUs are well-suited to this environment because they allow countries to start working together without waiting for a full treaty or formal legal agreement. The next sections will examine two examples where MOUs played this role.

The Bornholm Energy Island agreement between Germany and Denmark represents a shift in how regional energy cooperation is structured in Europe. The agreement is built around the concept of shared responsibility and mutual benefit. The two countries commit to dividing both the electricity produced and the infrastructure costs on an equal basis. Germany receives 50 percent of the renewable energy target amounts generated by the 3 GW offshore wind capacity, while Denmark takes on the primary responsibility for organizing the tender and issuing permits.3

This distribution helps prevent a structural imbalance. Since the wind farms will be built in Danish waters and connected to the Danish grid, Denmark would typically hold more influence over the project. But by assigning Germany an equal share of the output and aligning it with its national climate targets, the MOU equalizes the relationship and prevents future disputes over ownership, access, or control. This is legally supported by references to Directive (EU) 2018/2001, which enables EU Member States to engage in joint renewable energy projects and share target amounts.4 By embedding this directive into the agreement, the agreement becomes an instrument for fulfilling EU-wide obligations. The inclusion of legal language provides predictability to regulators and investors, while also giving the project legal relevance at the European level.

The role of Foreign Service professionals in this process is central but often overlooked. They are responsible for navigating the legal and administrative systems of both countries, coordinating between national ministries, and ensuring the agreement aligns with EU law.5 They also act as intermediaries between state-owned grid operators, whose cooperation is essential for the physical realization of the project. Through this coordination, diplomats helped interpret legal obligations, balance national interests, and secure institutional buy-in from different actors, demonstrating how energy diplomacy today is increasingly about shaping systems, not just negotiating deals.6

Another critical function of this MOU is how it prepares for uncertainty. The agreement includes structured procedures for dealing with delays, disruptions, and disagreements. Article 10 defines clear conditions under which force majeure may suspend obligations, while Article 11 establishes the European Court of Justice as the forum for legal disputes.7 By choosing this, the parties ensure that any disagreements will be resolved within a shared legal order, rather than through ad hoc arbitration. This reduces legal risk and creates confidence that the agreement will endure even under stress. In this sense, the MOU performs a stabilizing role, it reduces the risk that political or economic shocks will derail the project.

Importantly, the MOU does not try to anticipate every detail of future implementation.8 Instead, it creates a framework for ongoing dialogue. Annual meetings are required between the two governments and the transmission system operators to review progress, address technical changes, and consider legal updates.9 Here, too, Foreign Service officers play a strategic role. They manage the institutional relationship over time, ensuring that the agreement continues to serve the interests of both parties as conditions evolve.

In countries with weak energy institutions and limited investment infrastructure, energy diplomacy cannot rely on shared laws or integrated regional frameworks, as it does in the EU. Instead, it must begin by building the conditions under which cooperation and investment can occur.

This is the logic behind the MOU between Mongolia’s Ministry of Energy and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Unlike the Bornholm MOU, which aligns national policies with a shared EU climate strategy, the Mongolia-EBRD partnership focuses on constructing an institutional and regulatory foundation where none yet exists.10 The MOU is focused on designing a transparent and competitive energy market where state institutions, private developers, and foreign investors can operate with confidence. The ultimate goal is to create a predictable, rules-based process for renewable energy procurement in a sector that has historically lacked openness and efficiency.11

Mongolia’s energy sector is dominated by coal, reliant on outdated infrastructure, and burdened by the lack of competition in generation and supply. Though the country has ambitious renewable targets and immense wind and solar potential, these cannot be realized without a governance system capable of ensuring fair market access and safeguarding investor returns.12 The MOU responds to this gap by establishing a detailed roadmap for legal reform, procurement design, and stakeholder coordination, even if they are presented as technical assistance.

Career diplomats and international negotiators play a crucial role in this process. Their work involves helping the Mongolian government navigate institutional reforms while ensuring that any market-based solutions respect local conditions. For example, the agreement proposes the introduction of competitive auctions for renewable energy development.13 This mechanism acts as a signal that the government is willing to subject energy procurement to public scrutiny and international standards. Diplomats involved in the negotiation must ensure that this shift does not result in political backlash, regulatory confusion, or foreign dominance. Their job is to balance the need for market efficiency with the realities of domestic politics and administrative capacity.

Further, the agreement also introduces a new kind of diplomatic actor into the process: the consultant team tasked with drafting the legal and regulatory changes. These actors, while not traditional diplomats, are embedded in the agreement as intermediaries between local institutions and international best practices.14 Their assignment, as outlined in the terms of reference, includes designing the auction framework, proposing changes to legislation, recommending risk allocation models, and consulting with stakeholders through formal channels.15 This setup transforms what could have been a donor-driven initiative into a co-produced reform process. The creation of joint steering and working groups ensures that the Mongolian Ministry of Energy retains ownership while also benefiting from EBRD oversight and technical expertise.

The agreement also addresses the key problem of credibility. In fragile or transitional markets, one of the biggest barriers to investment is not the lack of resources but the lack of trust, i.e., trust in the fairness of the process, the stability of regulations, and the enforceability of contracts.

To resolve this, the agreement outlines concrete steps for de-risking investment, from setting technical qualifications and financial requirements for bidders, to defining clear timelines for project stages such as site selection, financial closure, and commissioning.16 The measures signal to international developers that Mongolia is creating an environment where energy projects can be built on time, paid for reliably, and operated securely.

Moreover, the MOU has a long-term diplomatic function. By promoting competitive bidding and regional export potential, it positions Mongolia as more than a beneficiary of foreign aid. It casts the country as a future energy exporter to its neighbors and as a responsible actor committed to its Paris Agreement obligations.17

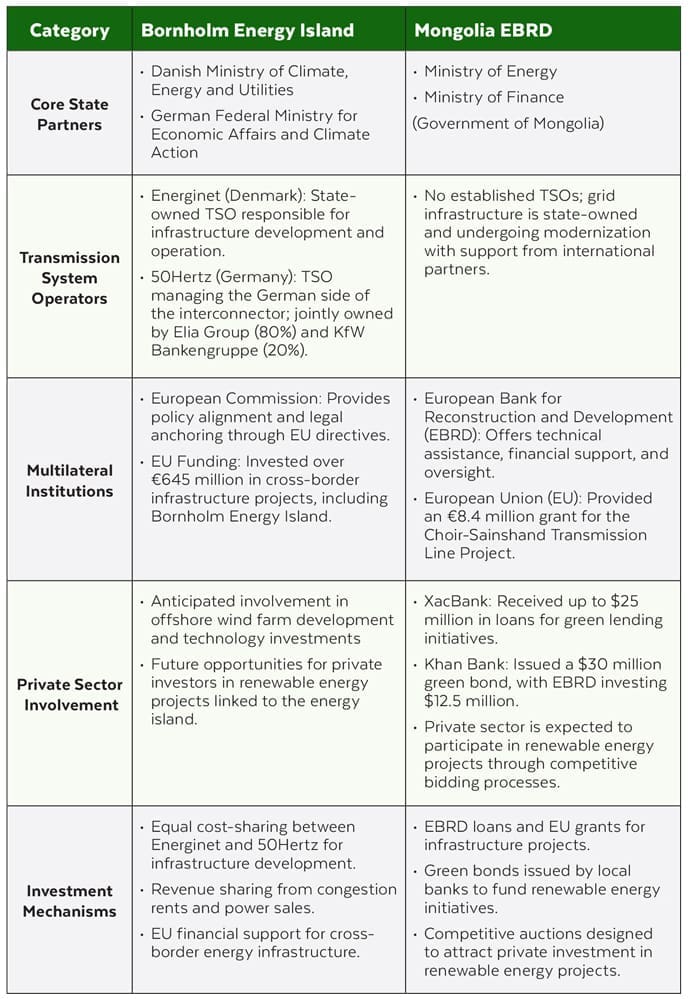

A comparison of both MOUs (in Figure 2) reveals that despite their contextual differences, both agreements treat diplomacy as infrastructure management, not just policy alignment. They are not informal or vague. Instead, they contain detailed procedural frameworks that address regulation, implementation, dispute resolution, and institutional coordination.18

One of the primary shared features is the phased implementation approach. Both MOUs structure their commitments into stages. In Bornholm, the agreement outlines the process for permitting, tendering, grid connection, and annual energy target reporting to the European Commission. It includes formal milestones, such as regular government reviews and shared notification obligations. The Mongolia – EBRD agreement takes a similar approach by requiring the design of a competitive procurement process, followed by specific legal reforms, and ending with the implementation of public auctions for renewable projects.19 Each phase is supported by consultant deliverables, such as legal drafts and final reports. These staged processes reflect a shared logic, cooperation must be sequenced to remain manageable and politically realistic.20

Another important shared element is the integration of public and private stakeholders. Bornholm formalizes collaboration between government regulators and privately owned grid operators. It anticipates future involvement by private technology firms and investors by embedding legal and permitting conditions that increase investor confidence.21 The Mongolia agreement goes further by specifying technical and financial requirements for bidders, such as demonstration of capacity, bid and development bonds, and permitting procedures.

It also proposes changes to model contracts and legislation, showing how the MOU is directly linked to investor readiness. This reflects a common feature of modern energy diplomacy: governments must work with private actors, but within structured, transparent frameworks.22

Finally, both MOUs treat diplomacy as a continuous activity, not a single event. Bornholm includes annual review mechanisms, formal energy accounting, and future cooperation possibilities under EU law. Mongolia includes long-term cooperation through the working group and iterative policy reform based on consultant outputs and steering committee feedback. In both cases, the MOU becomes open to adaptation but structured enough to sustain trust.

Ultimately, these case studies suggest that MOUs are not transitional documents. They are the operational core of modern energy diplomacy. They offer structured flexibility, ability to adjust to politics, absorb shocks, and hold institutions together across borders. Whether embedded in the legal order or deployed to build capacity in an emerging market, MOUs serve as infrastructural diplomacy: they organize how states, private actors, and international institutions cooperate across borders and time. More importantly, they signal a shift in diplomacy: from symbolic statecraft to system-building across public and private actors.

Valentini Pappa worked in the UK, Switzerland, and the USA with over 17 years of experience in university level educational environments. She has substantial experience on designing new curriculum. Pappa was with Texas A&M and TAMUQ as the Assistant Director of Graduate Studies. Now, she is the Program Director of New Initiatives with Georgetown at Qatar and also teaches the course Global Energy Transition. Pappa is also an Ambassador for the Clean Energy, Education and Empowerment Initiative of the U.S. Department of Energy.

References:

Andrea Tosatto, Xavier Martínez Beseler, Jacob Østergaard, Pierre Pinson, Spyros Chatzivasileiadis, North Sea Energy Islands: Impact on national markets and grids, Energy Policy, Volume 167, 2022, 112907, ISSN 0301-4215, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112907.

Bovan, Ana, Tamara Vučenović, and Nenad Peric. “NEGOTIATING ENERGY DIPLOMACY AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH FOREIGN POLICY AND NATIONAL SECURITY.” International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 10, no. 2 (2020): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.8754.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and Government of Mongolia. Support for Competitive Procurement of Renewables in Mongolia. 2022.

https://www.ebrd.com/sites/Satellite?c=Content&cid=1395276203647&d=Touch&pagename=EBRD%2FContent%2FContentLayout&rendermode=live%3Fsrch-pg%3Fsrch-pg%3Fsrch-pg

Government of Denmark and the Government of Germany. Agreement on the Realisation of the Joint Project Bornholm Energy Island for the Generation and Transmission of Offshore Renewable Energy. June 1, 2023. https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/J-L/joint-project-bornholm-energy-island-for-the-generation-and-transmission-of-offshore-renewable-energy.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6

Griffiths, Steven. (2019). “Energy Diplomacy in a Time of Energy Transition.” Energy Strategy Reviews 26 (July): 100386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2019.100386.

Huda, Mirza Sadaqat. “Renewable Energy Diplomacy and Transitions: An Environmental Peacebuilding Approach.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 50 (2024): 100815-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2024.100815.

Nergui, Otgonpurev, Soojin Park, and Kang-wook Cho. (2024). “Comparative Policy Analysis of Renewable Energy Expansion in Mongolia and Other Relevant Countries” Energies 17, no. 20: 5131. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17205131.

1 Huda, Mirza Sadaqat.(2024). p.10

2 Griffiths, Steven. (2019). p.4

3 Andrea Tosatto et al. (2022). p.10

4 Government of Denmark and the Government of Germany. Agreement on the Realisation of the Joint Project Bornholm Energy Island for the Generation and Transmission of Offshore Renewable Energy. June 1, 2023.

5 Griffiths, Steven. (2019). p.4

6 Andrea Tosatto et al. (2022). p.12

7 Government of Denmark and the Government of Germany. Agreement on the Realisation of the Joint Project Bornholm Energy Island for the Generation and Transmission of Offshore Renewable Energy. June 1, 2023.

8 Andrea Tosatto et al. (2022). p.11

9 Griffiths, Steven. (2019). p.4

10 Nergui, Otgonpurev, Soojin Park, and Kang-wook Cho. (2024). p.6

11 European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and Government of Mongolia. Support for Competitive Procurement of Renewables in Mongolia. 2022.

12 Nergui, Otgonpurev, Soojin Park, and Kang-wook Cho. (2024). p.4

13 Bovan, Ana, Tamara Vučenović, and Nenad Peric. (2020). p.6

14 Nergui, Otgonpurev, Soojin Park, and Kang-wook Cho. (2024). p.6

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibidd.

18 Huda, Mirza Sadaqat.(2024). p.9

19 Huda, Mirza Sadaqat.(2024). p.6

20 Ibid.

21 Griffiths, Steven. (2019). p.4

22 Huda, Mirza Sadaqat.(2024). p.6

Valentini Pappa worked in the UK, Switzerland, and the USA with over 17 years of experience in university level educational environments. She has substantial experience on designing new curriculum. Pappa was with Texas A&M and TAMUQ as the Assistant Director of Graduate Studies. Now, she is the Program Director of New Initiatives with Georgetown at Qatar and also teaches the course Global Energy Transition. Pappa is also an Ambassador for the Clean Energy, Education and Empowerment Initiative of the U.S. Department of Energy.