One hundred years is a major milestone and the observance of a centennial usually calls for a celebration but, with the world in the midst of a pandemic, there hasn’t been much fanfare as this year quietly marks the centennial of the first commercially producing well in the Permian Basin. Not the Santa Rita No. 1 (named after the patron saint of the impossible), which came on in 1923 and is often cited as the discovery well, but the Texas & Pacific Abrams No. 1, in Mitchell County, Westbrook, Texas.

The late Betty Orbeck, longtime director of archives for Midland’s Petroleum Museum, whose papers are housed in the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University, wrote a letter in 1995, supporting that assertion, and historical marker Atlas No. 5335001230 confirms Orbeck’s written account.

The text of the marker, which was reported missing in May of this year (and, hopefully, has since been recovered), reads:

The first commercial discovery oil well in the Permian Basin was named for W.H. Abrams, leasing agent for the Texas & Pacific Land Trust. The well first produced oil in February 1920 at a depth of 450 feet; but in June 1920, a better showing of oil was found at 2345 – 2410 feet. On July 16th, 1920 the well was “shot” with nitroglycerin. As a crowd of 2000 people looked on, a great eruption of oil, gas, water, and smoke shot from the mouth of the well almost to the top of the derrick. Shortly after, the well flowed at a rate of 129 barrels daily, but soon settled down to 20 barrels per day. From this well and a well nearby, the Rio Grande Oil Company laid the first commercial oil pipeline in the Permian Basin. The first load of oil went through the pipeline on April 3, 1922. W.H. Abrams No. 1 was re-designated on May 1, 1968 as Westbrook Southeast Unit No. 701, formed to increase oil recovery from the Westbrook Oil Field by water flooding. This enhanced oil recovery technique has produced 67 million barrels of the more than 100 million barrels of oil recovered from this field. Designated as major fields, only a small number produce 100 million barrels of oil or more. Fifty-six major fields are located in the Permian Basin, the fourth largest oil producing area in the US. (1967, 1996)

Author Tom Pendleton captured the ethos of Texas’s nascent petroleum industry in his novel, The Iron Orchard, which was published in 1966 to great acclaim, eventually earning it the nickname “the wildcatter’s Bible.” (While there are times when the book, now out-of-print, can be found for a reasonable price, it is not unusual to see it being sold online for hundreds of dollars.) Over 50 years – and a lot of false starts – later, a movie by the same name was finally released in 2018 (to far less enthusiasm), immortalizing the hardscrabble, sometimes violent, life in the oil fields in the early days of the “Wild West” Texas. While both were works of fiction, there certainly is no shortage of stories about real-life wildcatters and West Texas oilmen, like Michael Late Benedum, Joseph I. O’Neill, Jr., George Thomas Abell, and Clayton Williams, Sr., (and later his son, “Claytie”), who were involved in the frontier days of the Permian [see sidebar].

According to the Texas Railroad Commission (RCC), which gets its figures from the Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas, the greater Permian Basin now accounts for nearly 40 percent of all oil production in the United States and 15 percent of its natural gas. Last year, Forbes, based on numbers coming from Aramco, reported that the Permian had overtaken Ghawar in Saudi Arabia as the world’s top producing oil field in late 2018.

No oil-producing region, regardless how prolific, is immune to the vagaries of the cyclical petroleum industry, but the Permian Basin in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico seems to have somewhat of a Teflon® shield. During the 2014 bust when West Texas Intermediary (WTI) plummeted from a high on June 7th of $107.95/bbl. to $44.08 by January 28, 2015, the Permian appeared to be the one place that might emerge relatively unscathed.

The industry has been on a roller-coaster since then with WTI prices reaching as low as $27.94 on February 9, 2016, and as high as $75.30 on October 1, 2018, remaining fairly steady in the interim. After dipping to $42.53 on December 24, 2018, WTI rang in New Year 2020 at $63.27 on January 6th before the unthinkable happened on April 20th – the price of oil went into negative numbers for the first time since NYMEX oil futures began trading in 1983. The market corrected itself, as it normally does, and, as of this writing (August 14, 2020), WTI is currently at $42.01. (Source: EIA)

Producers in the Permian have proven, thanks in part to technical innovations – namely, horizontal drilling – that they can run leaner operations, drill more economically and, according the Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas, break even at around $50 a barrel, although that varies depending on location and other factors, but no one could have predicted the current situation the world finds itself in.

Previous scenarios don’t begin to compare to the economic, political and social upheaval in 2020, with a worldwide pandemic, oil price wars, unprecedented levels of unemployment, and the stock market crash. In oilfield terms, this is a bust of epic proportions. (“Downturn” doesn’t quite convey the sense of displacement that is reverberating through the industry and the world at large.) According to Haynes and Boone, which monitors oil and gas bankruptcies, over 30 companies have filed for protection during the first seven months of 2020, including some major players like Chesapeake, Denbury, Rosehill, and Sable Permian Resources, among others.

The average rig count, as reported by Baker Hughes, in August for District 8 (Midland) was 64 – far greater than that of any other district in Texas. The RRC reported that Midland independent exploration and production company, Summit Petroleum, LLC, filed for nine permits – the highest number the week of July 1st – 7th and a surprisingly high number in the middle of a crisis, as other companies scale back on drilling – for horizontal wells in Upton Co.

Even in times of disruption, the industry keeps innovating and making adjustments. One of the first refineries to be built in the U.S. since the late ‘70s is slated to be constructed by Meridian Energy Group, Inc. north of the town of Kermit in Winkler County, although according to the company’s website, it has “allowed its option on this site to expire while . . . evaluating potentially more viable alternative sites in the area.” The proposed one billion dollar, 60,000 bdp Walton Refinery (also known as the Permian Refinery) will be Meridian’s second (after the Davis Refinery in the Bakken in North Dakota) to operate under its new Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP), which aligns with the Equator Principles. As CEO William Prentice told Rigzone in February, not because it is being forced to by the government or in order to receive government funding or subsidies, but because “its founders and management team . . . wanted to create a firm that would be a profitable agent of change in cleaning up one of the most archaic and dirty segments of the energy industry.”

Even in times of disruption, the industry keeps innovating and making adjustments. One of the first refineries to be built in the U.S. since the late ‘70s is slated to be constructed by Meridian Energy Group, Inc. north of the town of Kermit in Winkler County, although according to the company’s website, it has “allowed its option on this site to expire while . . . evaluating potentially more viable alternative sites in the area.” The proposed one billion dollar, 60,000 bdp Walton Refinery (also known as the Permian Refinery) will be Meridian’s second (after the Davis Refinery in the Bakken in North Dakota) to operate under its new Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP), which aligns with the Equator Principles. As CEO William Prentice told Rigzone in February, not because it is being forced to by the government or in order to receive government funding or subsidies, but because “its founders and management team . . . wanted to create a firm that would be a profitable agent of change in cleaning up one of the most archaic and dirty segments of the energy industry.”

Another refinery, this one in Pecos County northeast of Fort Stockton, is being developed by MMEX Resources Corp. to process lighter crudes. In addition to a 10,000 bpd crude distillation unit (CDU), there will be a 100,000 bpd facility producing transportation-spec fuels.

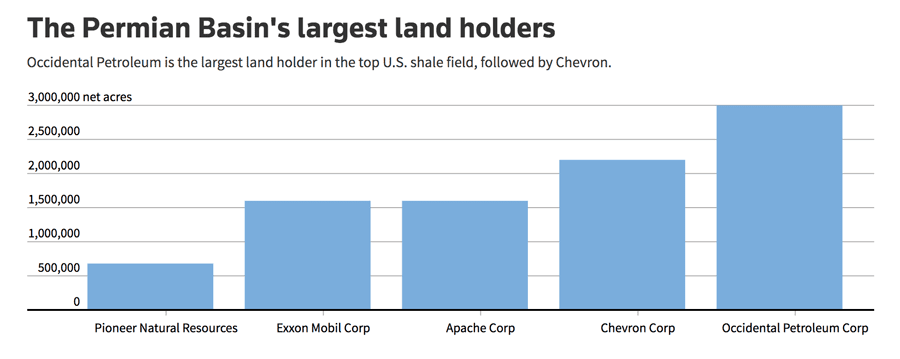

The headline-dominating news to come out of the Permian was last year’s acquisition of Anadarko – and its 240,000 acres – in a gutsy move by Occidental Petroleum CEO Vicki Hollub. After a bidding war with Chevron over the prized acreage and production, and a protracted battle with billionaire activist investor Carl Icahn, Oxy emerged victorious, becoming the largest landholder in the Permian with three million net acres. On August 8th, the date of the closing, Oxy’s stock opened at $46.57; as of this writing, it is priced at $13.82. Hollub has made it clear in interviews that she believes the Permian will continue to be a major contributor to the country’s energy resources, as she told Time in January 2019, “for many years to come,” something she reiterated in similar terms at the recent Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) virtual conference in July.

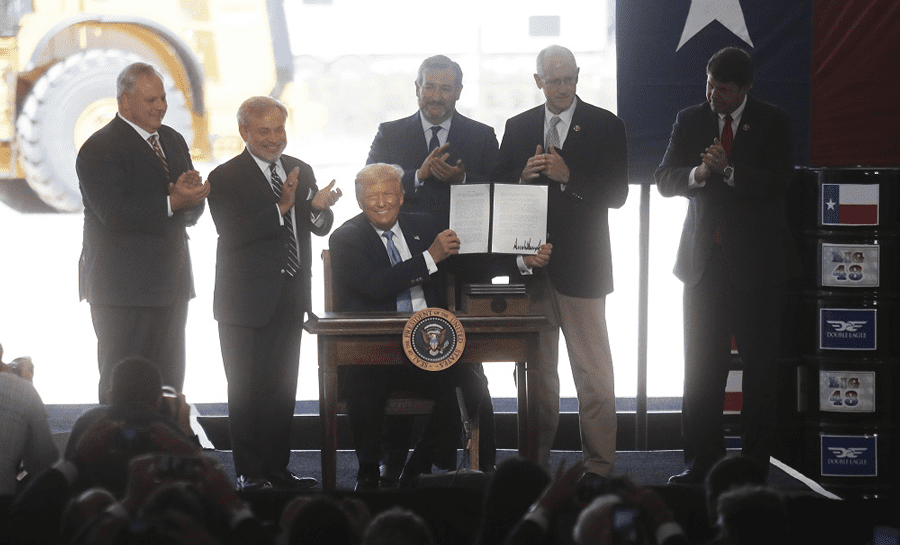

West Texas was the site of a late July campaign fundraising trip by President Donald Trump, where he gave a speech at a $2,800 a plate private luncheon held at the Odessa Marriott Hotel (for $50,000, couples could have their photo taken with the president and for $100,000 per person sit at a roundtable with him). According to the Odessa American, the event raised about $7 million. After the fundraiser, President Trump signed four permits that will allow for the expansion of pipelines and railroad infrastructure, including two that will provide for crude from Texas to be exported to Mexico. He then went back to Midland, where he had flown in, to visit a rig site owned by Double Eagle Energy.

The area is no stranger to presidential visits. After President Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration, President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush flew to Midland, where Bush had worked in the oil industry prior to entering politics, to mark the end of his two terms as president. In 2012, President Obama stopped in the tiny town of Maljamar, near the larger towns of Hobbs and Carlsbad, in Lea County, part of the Permian Basin that extends into New Mexico. He then traveled to oil and gas production fields located on federal lands in the area, which were the site of more than 70 active drilling rigs at the time.

The attention to the Permian by presidents from both parties only serves to underscore the region’s importance to America’s energy strategy 100 years after the Texas & Pacific Abrams No. 1 gave the nation a glimpse of the potential it held for the future.

Harsh Country, Hard Times: Clayton Wheat Williams and the Transformation of the Trans-Pecos

By Janet Williams Pollard and Louis Gwin

Chapter 8: Drilling the University No. 1-B Well

When the University 1-B well finally struck oil at 8,525 feet on December 1, 1928, Clayton [Williams, Sr.] was not there to see proven his hypothesis that commercial quantities of oil did exist at deeper levels in the Permian Basin. He had resigned from Texon on August 1st having become engaged to be married. He would later say that he resigned because he did not want to raise a family in the rough world of the oilfields. Clayton had hired his brother Waldo as an assistant engineer in 1926, and Waldo was on the site during the last few months of drilling.

When the University 1-B well finally struck oil at 8,525 feet on December 1, 1928, Clayton [Williams, Sr.] was not there to see proven his hypothesis that commercial quantities of oil did exist at deeper levels in the Permian Basin. He had resigned from Texon on August 1st having become engaged to be married. He would later say that he resigned because he did not want to raise a family in the rough world of the oilfields. Clayton had hired his brother Waldo as an assistant engineer in 1926, and Waldo was on the site during the last few months of drilling.

The story of the completion of the University 1-B is a part of Texas oil history lore. According to both [author and historian Samuel D.] Myres and Waldo, [Frank] Pickrell decided that enough money had been spent on the project and ordered [Carl] Cromwell to stop drilling at 8,500 feet. “Carl accepted the order,” Waldo wrote, “but later when talking over the prospects of a producer with me, he suggested that he disappear without telling me the order to shut down and that I carry on down until we had a producer or a dry whole. On December 1st, the bailer would not go down against the gas pressure and on the 2nd of December the well flowed 40 barrels of high gravity oil.”

It took Waldo and the crew two days to locate Cromwell, who was drinking heavily in Sweetwater, Texas. “However, he was sober the minute he absorbed our message and within five hours was on the ground in efficient charge of the situation.” By January 1, 1929, University 1-B was producing more than 1,600 barrels a day of high-quality oil and, according to Myres, proved the practicability of deep wells both in the Big Lake field and elsewhere in West Texas.

Locating the University 1-B was the most notable achievement in Clayton’s oilfield career and provided the foundation for his reputation as one of the Permian Basin’s significant petroleum engineers. He did not boast about the discovery in his personal papers and letters, writing only specific details associated with the location and drilling of the well. But he was fiercely proud of the discovery, [daughter] Janet Pollard says. “I remember one Christmas after I was married, we were in Fort Stockton at Daddy’s house and a man dropped by. This man had recently had some success in the oilfields, and he was talking about various wells including the University 1-B. ‘I located that well,’ I remember my dad said, and the man replied, ‘The hell you did.’ My dad got very angry, stood up and said, ‘The hell I didn’t.’ I thought he was going to get into a fight, but the man backed down and apologized.”

Excerpted with permission from the author. Harsh Country, Hard Times: Clayton Wheat Williams and the Transformation of the Trans-Pecos by Janet Williams Pollard and Louis Gwin (Texas A&M University Press; September 1, 2011).

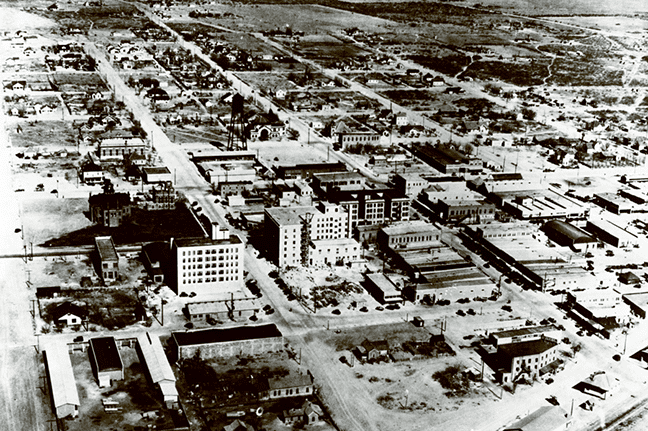

Headline photo: Aerial View of Midland, Texas, 1928. Photo courtesy of The Petroleum Museum, Abell-Hanger Foundation Collection

Rebecca Ponton is the editor in chief at U.S. Energy Media and author of Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. She is the publisher of Books & Recovery digital magazine.