With the price of oil set by world oil supply and demand, watching not only how much oil countries are producing and using today, but also what those numbers will look like in the future is a critical practice for industry members. The current thinking is that demand has increased, somewhat, and supply could – depending on the approach in certain regions – decline. If those numbers keep on that track, the price of oil will go back up from the record lows seen in the past year. Should that be the case, however, some wonder whether there is an inherent cycle in play that could undo a long-term upswing.

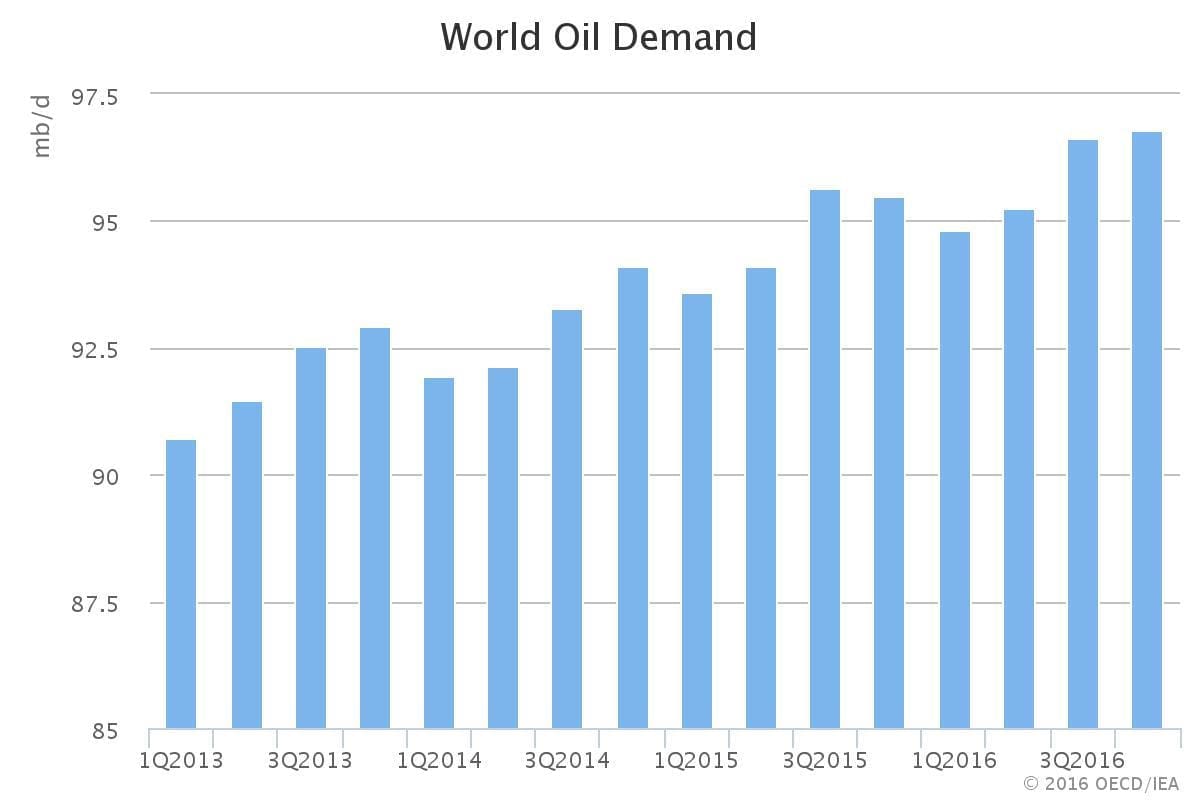

In April, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released its figures on global oil supply and demand showing that, despite clear growth in global demand, growth will ease to about 1.2 million barrels per day (mb/d) this year. That forecast is below 2015’s 1.8 mb/d expansion, which, according to the IEA, is due to notable decelerations in China, the U.S. and Europe. IEA said that preliminary 1Q16 data show the easing of demand growth is already occurring, with year-over-year growth down to +1.2 mb/d, after gains of +1.4 mb/d in 4Q15 and +2.3 mb/d in 3Q15.

“With lower prices there’s no doubt that demand has increased over the past 18 months,” Russell Braziel, CEO of RBN Energy, told Oilman. “We can tell from looking at the price, demand hasn’t increased enough to make that much of a difference, but it has increased, and because it has increased then the supply response doesn’t have to be as significant as it would have to be otherwise.”

In addition to the increase in global oil demand, supply has decreased with a slight decline in the production of crude oil.

In the U.S., Braziel said, the rig count is falling off extremely fast.

“We are at record low levels of rigs running, and because of that, crude oil production in the U.S. is going to start declining faster,” he said. “The view is that U.S. crude oil production from December 2015 to December 2016 will probably fall off in the neighborhood of 1 mb/d. That’s a lot.”

As that happens, he added, it is likely that the supply-demand balance will start tracking up and crude oil prices will increase.

The outlook from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) follows with Braziel’s estimates.

In its April outlook, EIA said that U.S. onshore crude oil production in the lower 48 states is expected to decline from an average 7.4 mb/d in 2015 to 6.46 mb/d in 2016 and to 5.7 mb/d in 2017. EIA also said that although there will be an increase in production in the Gulf of Mexico, that increase will not be enough to offset onshore declines, with total projected U.S. production falling from 9.4 mb/d in 2015 to 8 mb/d in 2017.

Braziel is an authority in the field of energy markets and the author of the book The Domino Effect: How the Shale Revolution is Transforming Energy Markets, Industries and Economies. Released in January, The Domino Effect examines energy markets and the events of the shale revolution that influenced future events in those markets.

“Every step of the way, every event in the shale revolution, happened for a reason, and every event happened because of something that happened before it,” Braziel said. “So one domino falls on another domino, which falls on another domino. I identified 30 of those dominos that have happened basically since the inception of the shale revolution 10 years ago and explained how each of those dominos was toppled by something that came before it.”

In the course of telling the story of the shale revolution and its effect on energy markets, Braziel identified certain patterns over time.

“It became apparent that these events weren’t just happening randomly; they were happening for a set of reasons,” he said. “I identified six reasons – or six principles – that, because these six principles exist, the [crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids] commodities are related to each other in ways that they haven’t been before.”

Braziel said that with an understanding of those six principles comes an understanding of why those “dominos” of the shale revolution have fallen, and more importantly, what dominos are going to be falling in the future.

The Problem

Braziel cautioned that there is one potential – and likely – future that could result from current market dynamics.

The fall in rig counts and reduction in drilling in the U.S., he explained, is due to low oil prices that cause poor economics for drilling and production. What happens, he asked, when prices go back up?

“If prices go back up to say $50 or $55, then those economics start looking very good again,” he said. “The big question is not whether that is going to happen – I think pretty much everyone has concluded that that is a relatively likely scenario – but when prices do go up, and producer economics start looking good again, is it likely that producers will jump right back into the oil patch and start drilling again, hire as many new people as they can, bring the rigs back online, and start production growth all over again?”

Given a business-as-usual scenario in global supply and demand, as soon as production rebounds to 9 mb/d, oil prices will come right back down, he said.

“In my view, we’re in a cycle,” he said. “If prices go up high enough, then production is going to respond over some period of time – it’s not going to be instantaneous – but producers are going to respond to those higher prices. They’re going to drill more and when they do, prices will come back down again.”

The main factor that is different than any other time period in the history of the U.S. oil industry, he added, is that the producers know exactly where the oil is now.

“All they need is a price signal that’s strong enough for them to drill it. It’s almost like the oil is in storage,” he said.

When the U.S. oil industry receives the right price signals to tap those resources, the companies positioned to grow will be those that are ready right now to take advantage of the slow market.

“For energy companies, for producers, the world divides up now into the winners and the losers,” Braziel said. “The winners are producing in the right locations, in good counties with the right economics, they didn’t over extend themselves, they have good balance sheets, and they can take advantage of some assets that are on the market or will be on the market, and they will be able to buy into the energy opportunities at prices that will be fabulous for their companies.”

The catch, he added, is that those low-price assets are going to come from the companies that didn’t position themselves well for the downturn.