Back in 2014 they were unlikely adversaries. Saudi Energy Minister Ali Al-Naimi, and Pioneer Natural Resources (PXD) CEO Scott Sheffield had both made their careers in the oil business. They had each spent formative years abroad, with Al-Naimi attending Lehigh University and Sheffield going to high school in Iran (his father worked for Atlantic Richfield). Both were dedicated to maximizing the value of the fossil fuels they controlled, and had hunted together (a common pastime for oilmen).

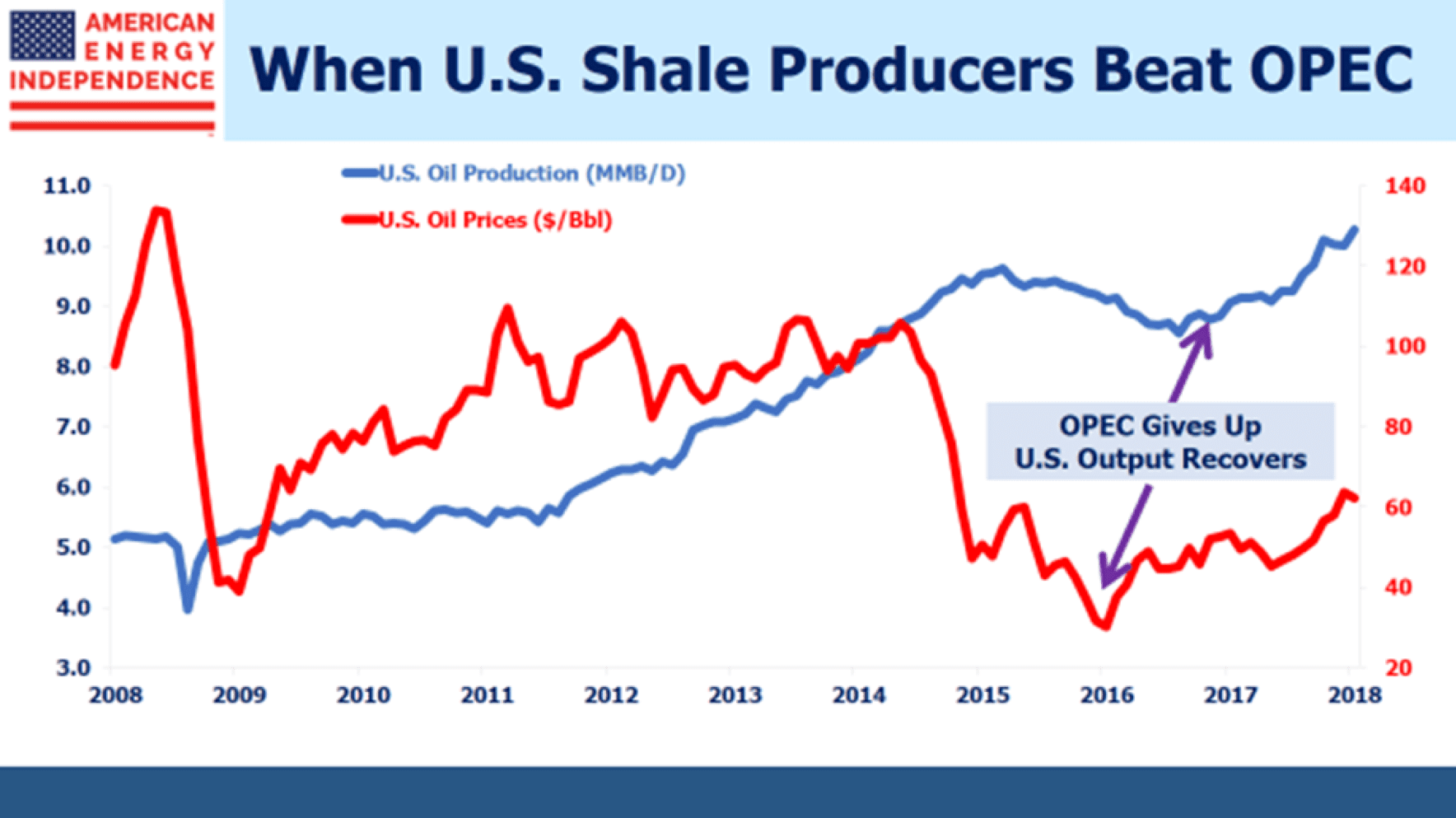

But the success of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in the U.S. was releasing increasing amounts of crude oil from hitherto impenetrable porous rock. A consequence was that from 2011-2014 fully all of the increase in global demand for crude oil had been met by North American production. This was hurting prices and reducing OPEC’s market share. Al-Naimi concluded that the interlopers were vulnerable to a drop in prices that would expose their high cost structure. Pioneer was one of the biggest producers of shale oil. They had been deemed “The Motherfracker” by hedge fund manager David Einhorn who likened their low return on capital to, “…using $50 bills to counterfeit $20s.” Scott Sheffield’s business and others like it were increasingly at odds with OPEC, and Al-Naimi decided they needed to be stopped.

So it was that in late 2014 the Saudis shocked the oil market by promising to increase production into an already oversupplied market, rather than adopt their familiar role of swing producer, modifying their own output to smooth price swings. They calculated that lower prices would bankrupt large swathes of the U.S. shale oil industry, eventually cutting production and allowing prices to return to the $100+ levels necessary to support Saudi Arabia’s budget. “We are going to continue to produce what we are producing, we are going to continue to welcome additional production if customers come and ask for it,” al-Naimi said.

What followed is one of the most extraordinary stories of private sector innovation in the biggest, most dynamic economy the world has ever seen. Crude prices plummeted, falling as low as $26 a barrel on February 11, 2016. Facing an existential threat to their businesses, Pioneer and many companies like it drove production costs down relentlessly, bringing break-evens down to levels few had thought possible.

U.S. production dipped but didn’t collapse. OPEC expected a quick victory, with widespread bankruptcies among shale producers leading to production cuts and higher prices. It didn’t happen, and the damage to member budgets mounted.

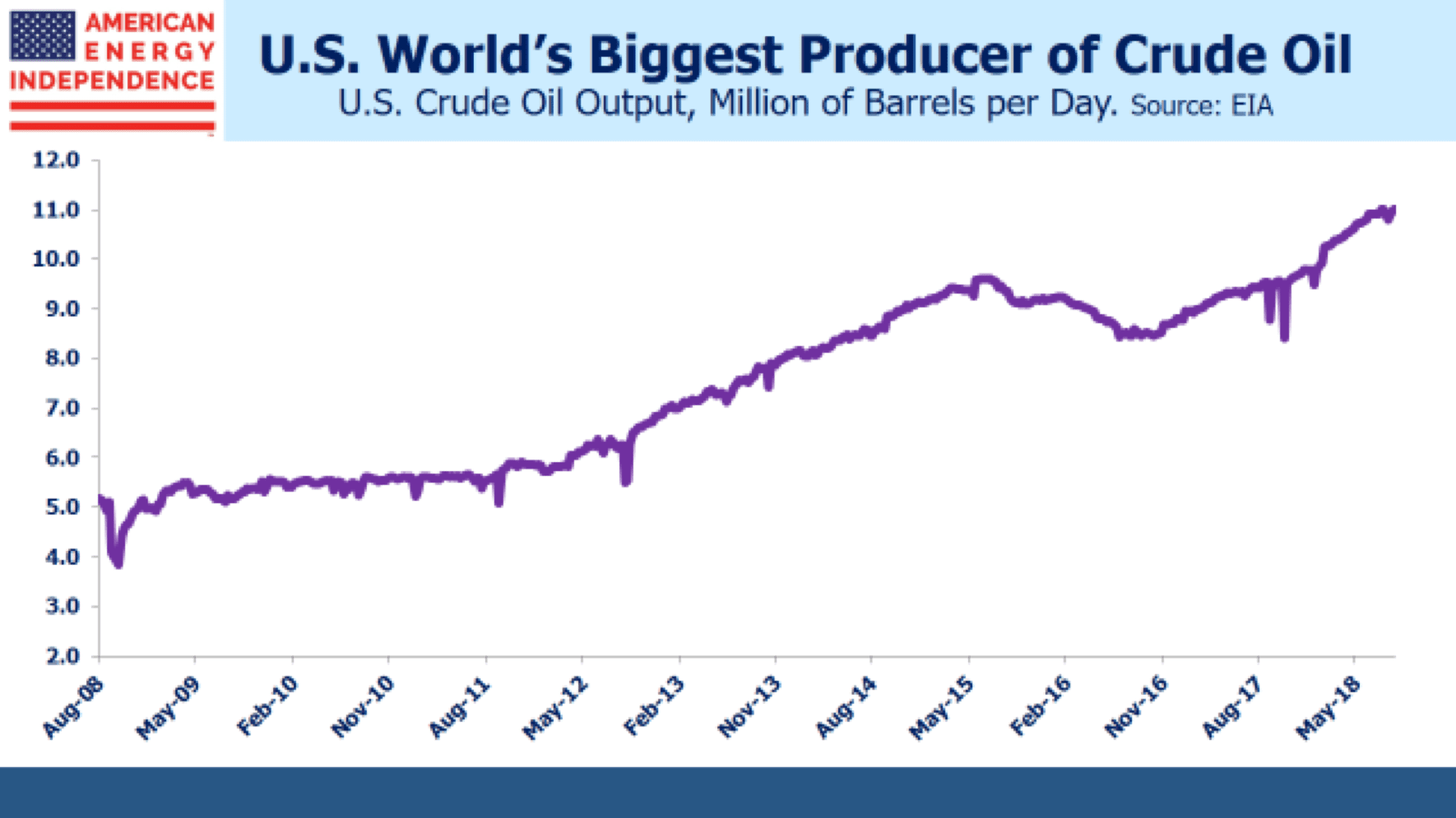

In late 2016 OPEC relented, concluding low prices were damaging their members more than the shale upstarts. U.S. production began rising again. Earlier this year we took the world’s top producer spot, well ahead of many forecasts.

It was a significant, far-reaching victory for America’s shale producers.

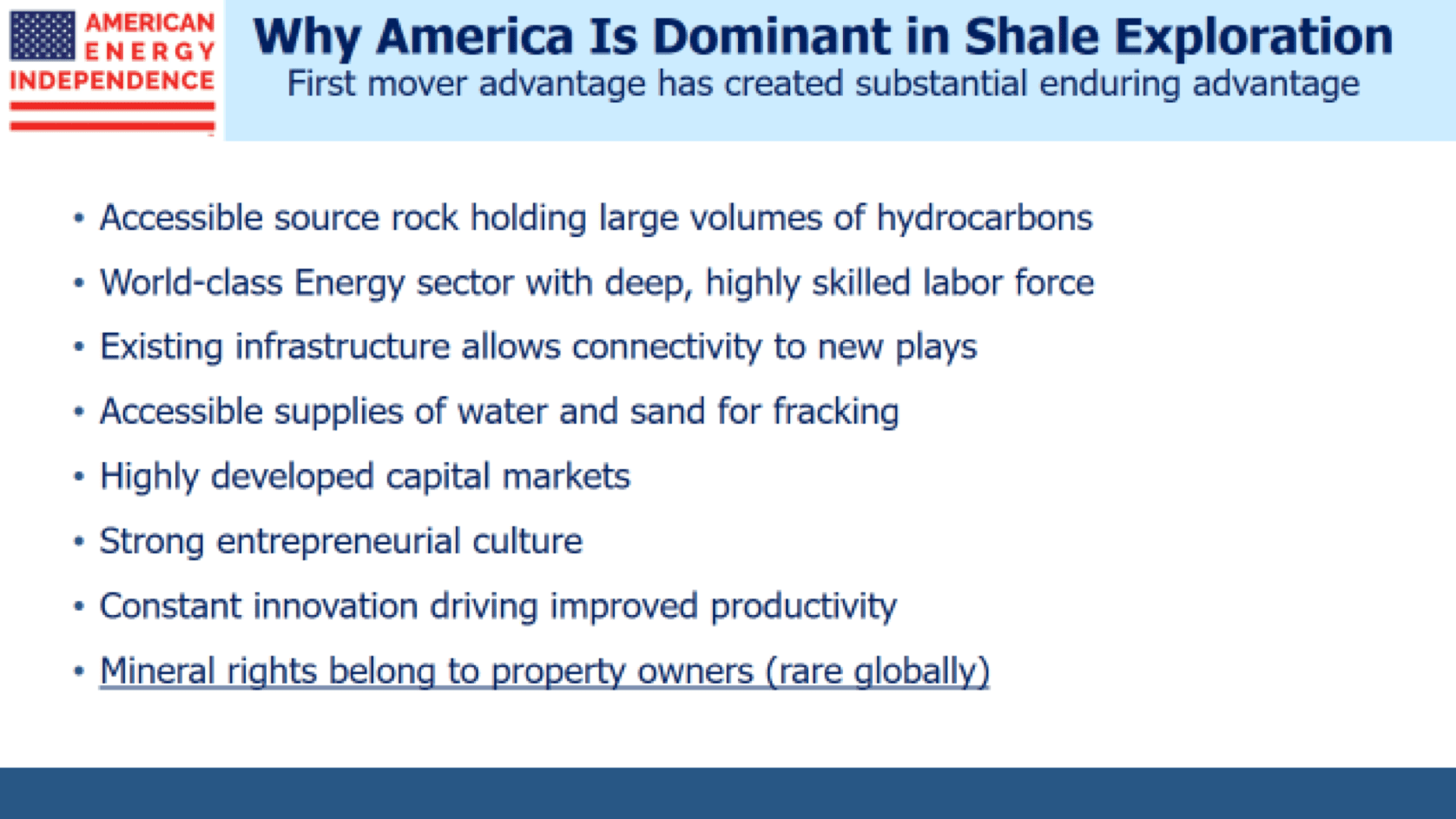

U.S. shale oil and gas production are upending the energy markets. The U.S. is not just the leader in this new technology, it’s virtually the only game in town. Oil, natural gas liquids and natural gas are known to exist in porous rock all over the world, notably in China and Argentina. America’s dominant position reflects many inherent free market advantages in the world’s biggest economy which are not sufficiently present elsewhere.

Start with a large energy sector already adept at exploiting conventional resources, with a deep pool of skilled labor and long history of technological improvement. Add to this: access to capital from the world’s biggest capital market; a strong entrepreneurial culture; existing energy infrastructure that can be modified and enhanced to service these new regions of output; ample water and specific grade sand supplies (needed for fracking), often conveniently located; mineral rights that belong to property owners, unknown in other countries but taken for granted in the U.S., which builds community acceptance of drilling activity that creates local wealth.

Only the U.S. combines all these advantages. The result is that cheap natural gas now produces more electricity than coal, and we’re a net exporter. We’ve even shipped it to the United Arab Emirates, because it’s cheap enough to cover the transportation costs.

Natural gas from U.S. shale was developed under a much higher price regime, which allowed time for scale that could lower costs as global Liquified Natural Gas supplies weighed on prices. Similarly, the development of crude oil sourced from shale started when prices were higher, so the industry was subsequently mature enough to adapt to falling prices. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing of rock could not have developed as they did under today’s hydrocarbon price regime. OPEC’s strategy was correct but several years too late. There is no going back.

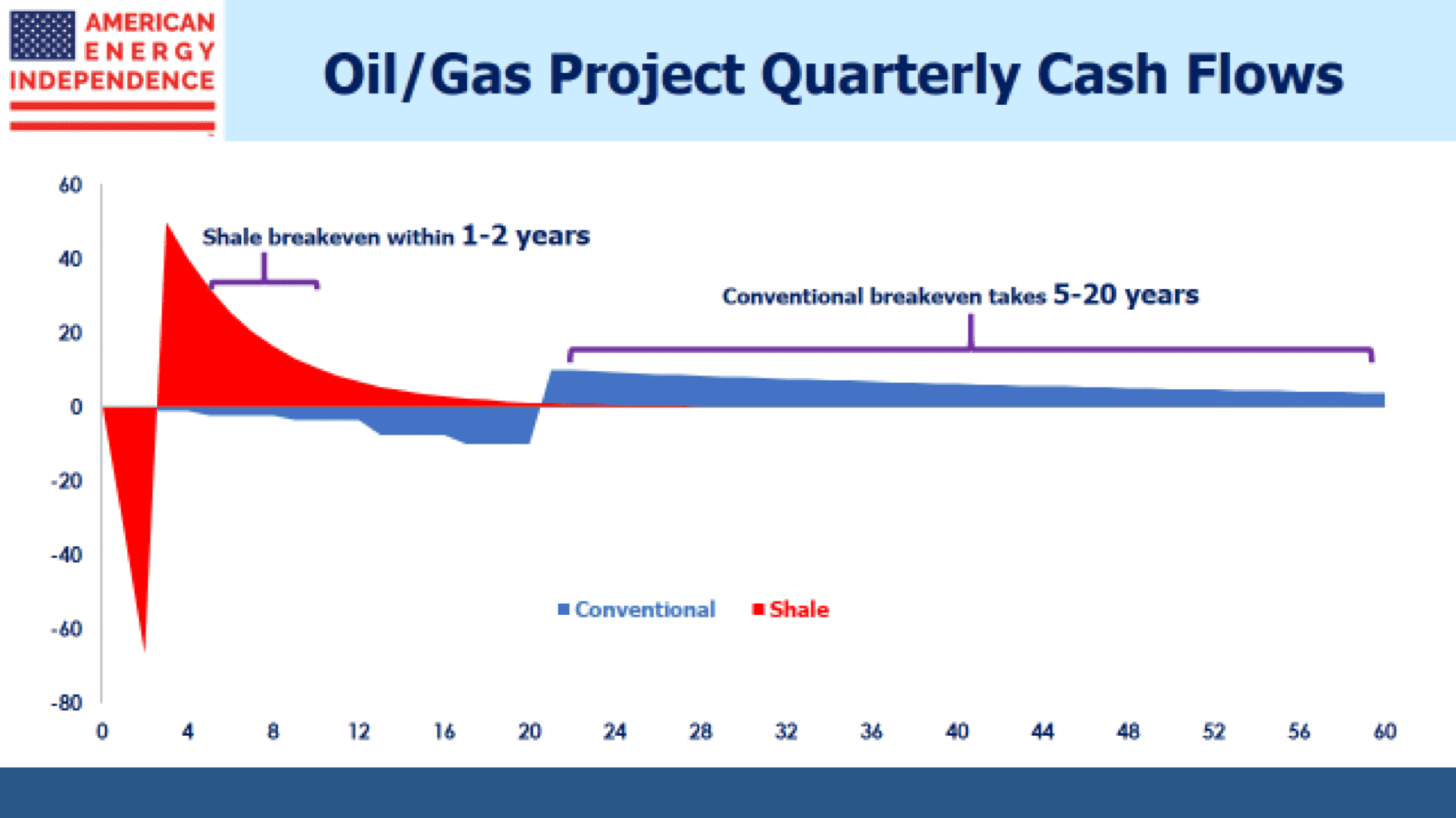

Moreover, in crude oil the U.S. is now the global swing producer. To see why, consider the thinking behind the $1 trillion in cuts to exploration budgets. Conventional oil projects involve a large up front capital commitment with a long payback period, during which the overall profitability will be exposed to oil prices. Since the futures market only offers liquidity out to 2-3 years, oil drillers are basically long the oil market.

Assessing this risk now includes the 2014-16 oil price collapse which damaged the IRR on many prior investments. A previously uncontemplated oil price is preventing many new projects from being funded, because it might repeat. Yet the U.S. shale producer, ostensibly the instigator of the excess supply, pursues many small projects with minor upfront expense (a horizontal well now costs on average less than $5 million) mitigating individual risk. U.S frackers may forego the significant cost of completing a drilled well in response to lower prices, resulting in an inventory of DUCs (Drilled UnCompleted wells) awaiting higher prices. Capital is recycled faster.

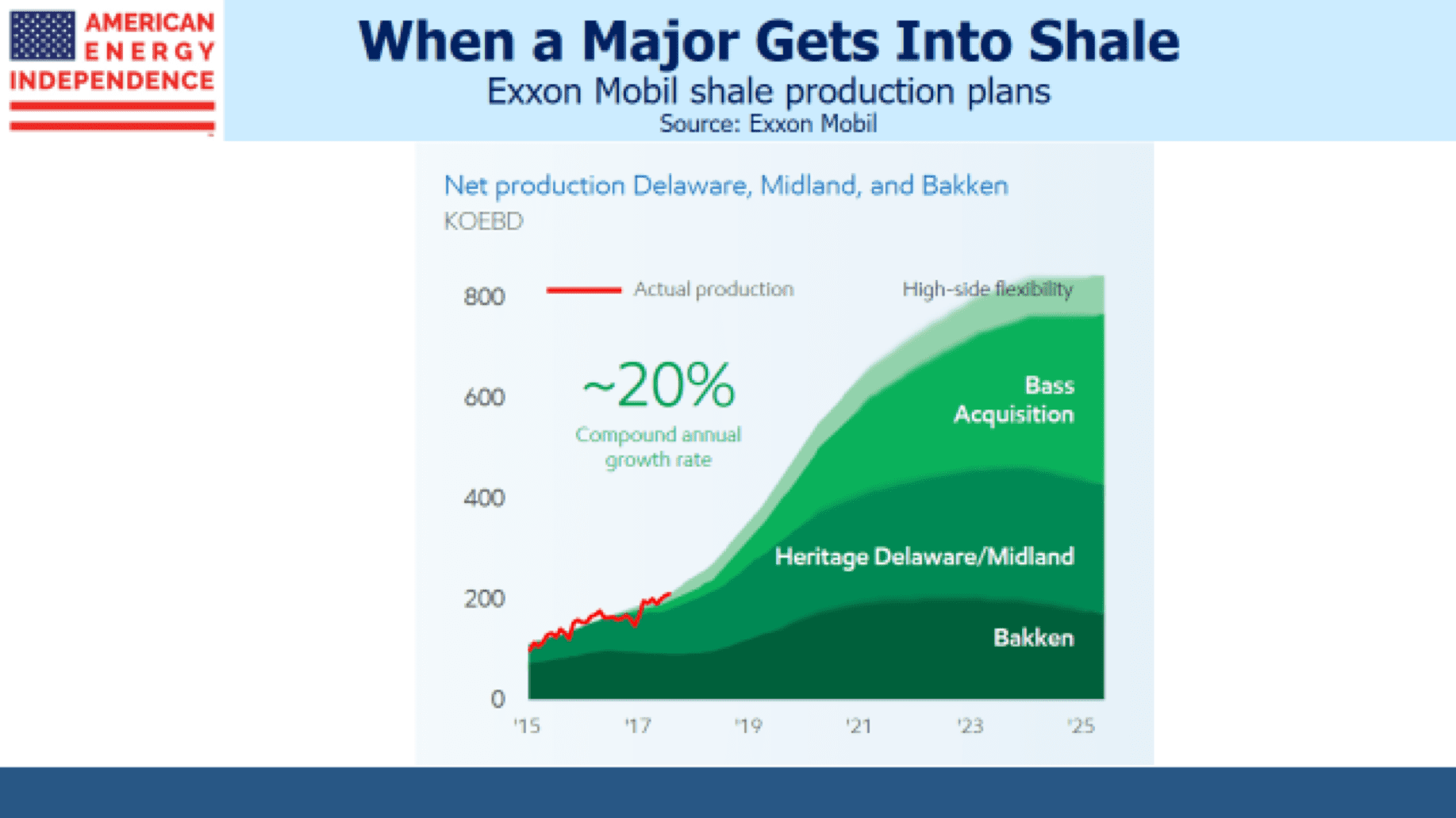

The short-cycle nature of shale provides a significant lower risk profile for producers. Earlier this year, when Exxon Mobil (XOM) announced plans to invest $50 billion in the U.S. over the next five years. CEO Darren Woods singled out the Permian Basin in West Texas and New Mexico as an important target for some of this capital investment. It’s evidence that the world’s biggest energy companies recognize the value in the Shale Revolution. Unconventional “tight” oil and gas formations offer rapid payback for a small initial investment. Capital invested is often returned within two years, allowing price risk to be hedged in the futures market.

As a result, earlier this year the U.S. became the world’s biggest crude oil producer.

This represents a milestone in the path towards American Energy Independence. Only seven years ago, U.S. output was less than six million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) and was in decline. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing unlocked the huge reserves in shale formations, and the decline was arrested. The EIA is now forecasting 2019 production of 11.8 MMB/D.

It’s an epic story, with significant consequences across geopolitics, trade and the environment. America’s improved energy security is underwriting a more robust approach to Iran. In the 1970s, support for Israel in its wars against Arab states led to gas lines as OPEC flexed its muscle and imposed an oil embargo.

American exports of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) are creating new trade opportunities with Asia, where South Korea, China and Japan are among our biggest buyers. In spite of the escalating tariffs with China, they recently exempted U.S. crude oil imports from a list of items subject to new tariffs. Germany’s plan to buy more natural gas from Russia via Nord Stream 2 is more easily criticized when U.S. LNG is available. Trump’s tweet, “What good is NATO if Germany is paying Russia billions of dollars for gas and energy?” is hard to fault.

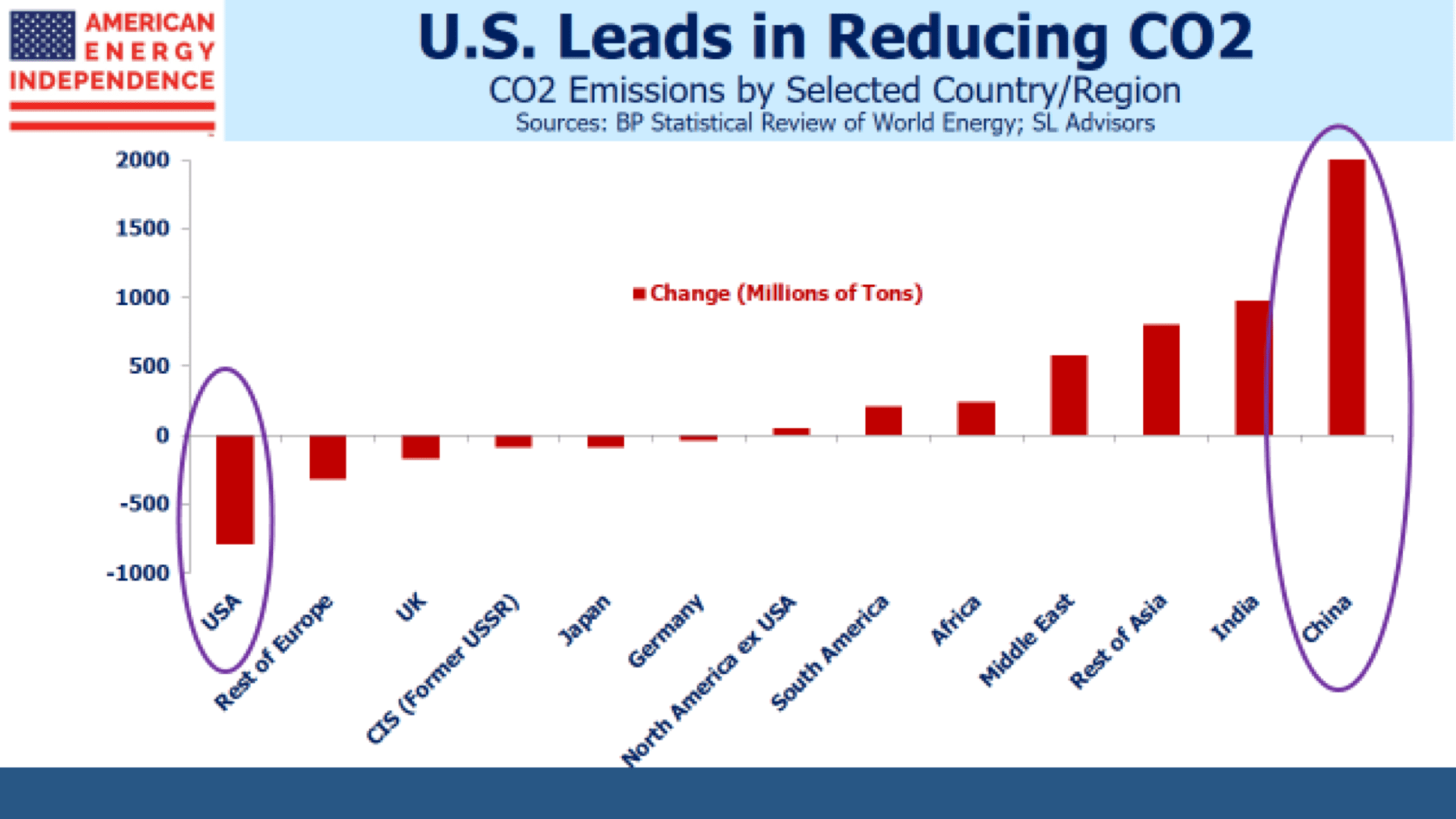

American Shale gas has also contributed to the world’s biggest reduction in CO2 emissions. It’s made possible the shift from coal to natural gas in electricity generation. The Shale revolution has been positive in so many ways.

All this means that the Shale Revolution was not luck. The world’s biggest and most dynamic economy made it possible. If it was going to happen anywhere, it was going to be in America.

Illustration and graphs courtesy of Catalyst Funds

Simon Lack is Portfolio Manager at Catalyst MLP and Infrastructure Fund.