Predicting oil prices is notoriously difficult because oil prices reflect both supply and demand dynamics. Of course, supply issues garner the lion’s share of the media’s attention – often around geopolitical shocks – and are inherently unpredictable.

Nevertheless, in reality, the demand side of the equation dominates sustained swings in oil price inflation. Having studied such cyclical dynamics for decades, we have a clear understanding of the cyclical drivers of global oil demand to help us distill whether moves in oil prices are supported by directional shifts in demand growth, or are merely reflective of supply-driven gyrations. When global economic growth slows, oil demand growth follows suit. Such swings in oil demand can also show up with a lag in measures closely followed by industry participants, including growth in rig count.

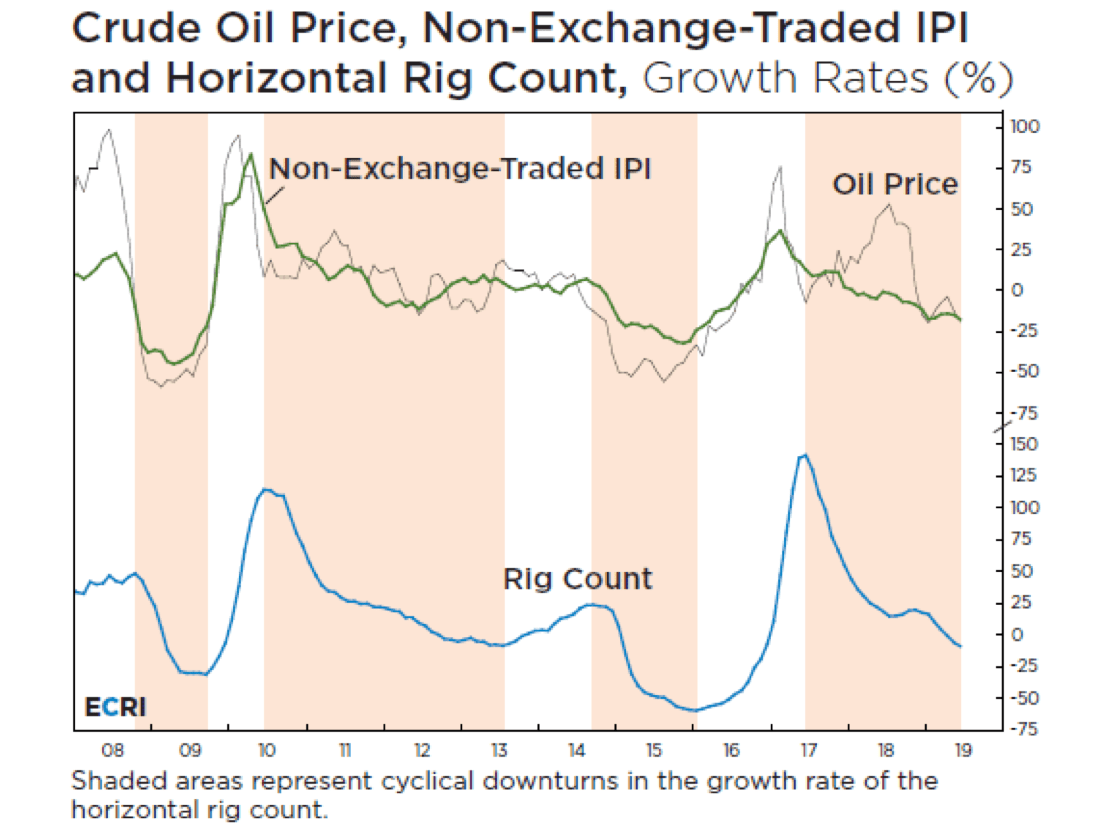

Another key cyclical insight is that the trajectory of oil price inflation – the growth rate of oil price – tracks broad industrial raw materials price inflation, where cyclical demand is clearly the overwhelming driver of price action (see chart). Today, regardless of additional supply disruptions, the cyclical demand dynamics that underlie oil price inflation point to more near-term weakness ahead.

No doubt, oil prices are swayed by supply-related news on a day-to-day basis. This is not only because of very real, transitory supply distortions, but also because oil is an exchange-traded commodity subject to speculation. To see through these issues, our research group splits a set of sensitive industrial materials prices (that we have tracked on a daily basis for over 30 years) into two groups. One group consists of exchange-traded commodities, including oil, copper and nickel, and the other is comprised of their non-exchange-traded counterparts, such as natural gas, hides and steel. Most of the time, the prices of the exchange-traded and non-exchange-traded commodities move together, but they can diverge sharply on occasion. Because non-exchange-traded raw material prices are shielded from speculative forces, their prices more accurately reflect the predictable fluctuations in demand that are driven by cycles in global industrial growth.

For example, around the onset of the Arab Spring, in early 2011, there was a spike in oil price inflation, while non-exchange-traded commodity price inflation continued falling. These were in line with a cyclical slowdown in industrial growth. More recently, the behavior of those prices has also been telling, with regard to those underlying demand dynamics. While raw material commodity price inflation has mostly been declining since the start of 2017, oil price inflation followed suit only through mid-year, when OPEC supply cuts took hold, boosting oil prices. This divergence held through most of 2018 until, as worries about global demand mounted late last year, oil price inflation tumbled back in line with that in non-exchange-traded commodities. Then, following the Fed’s dovish pivot in January, oil prices participated in the speculative risk-on rally, only to reverse course yet again.

Thus, despite its wild swings, oil price inflation is actually well-anchored to the smoother and more predictable cyclical swings in non-exchange-traded commodity price inflation. It is almost as if those non-exchange traded prices act as a trend line from which oil price inflation may temporarily deviate. Therefore, when there are sharp directional divergences between the two measures of commodity price inflation, supply-related or speculative distortions are likely at play.

In other words, when oil price inflation spikes or plunges again, in the wake of speculation about supply or risk-on sentiment, a dangerous or fortuitous moment may be at hand. To understand which one it is, it pays to check what the non-exchange-traded commodity prices are signaling about where we are in the industrial demand cycle.

Lakshman Achuthan is the co-founder of the Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI). He also serves as the managing editor of ECRI-produced forecasting publications. Over nearly 30 years of analyzing business cycles, he has been featured in the Wall Street Journal, FOX Business News, the Washington Post, Forbes and many other publications. He is also a frequent guest on business and financial news programs on CNBC, Bloomberg, Reuters and MSNBC. Achuthan has been a featured speaker at John Mauldin’s Investor Conference and the Levy Institute’s Minsky Conference. In 2004, he co-authored Beating the Business Cycle: How to Predict and Profit from Turning Points in the Economy.

Achuthan met his mentor, Geoffrey H. Moore, in 1990 and was immediately fascinated by Moore’s unique global approach to analyzing business cycles. After working together for years, with co-founder Anirvan Banerji, the three left Columbia University to start ECRI in 1996.

Achuthan currently serves on the Board of Economists for Time Magazine, on the Board of Governors for the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, and as a trustee on the boards of several other foundations. He received an undergraduate degree from Fairleigh Dickinson University and a graduate degree from Long Island University. Follow him onLinkedInand on Twitter at@businesscycle.

Anirvan Banerji is the co-founder of the Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI). Additionally, he is the editor-in-chief of ECRI’s forecasting publications and is the co-author of Beating the Business Cycle: How to Predict and Profit from Turning Points in the Economy. Banerji has been an invited speaker at events ranging from the Eurostat colloquium on modern tools for business cycle analysis to the Grant’s Interest Rate Observer conference.

Banerji worked closely with Geoffrey H. Moore since 1986 at Columbia University's Center for International Business Cycle Research and co-founded ECRI with Moore and Achuthan in 1996. Banerji currently serves on the New York City Economic Advisory Panel and is also a past President of the Forecasters Club of New York. He has an engineering degree from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur and graduate degrees from the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad and Columbia University.