Conversations around the negative consequences of oil and gas production tend to center on methane. There are very sensible reasons for this: methane contributes significantly to climate change and leads to a panoply of other environmental effects. But all of that attention tends to obscure another, arguably equally important consequence of oil and gas production: namely, the issue of produced water.

You may know produced water by its more common name—i.e., brine. It is one of the many byproducts of oil and gas production, and it forms when shale rock releases hydrocarbon molecules. Though relatively under-discussed, some experts have called it the greatest challenge facing the oil and gas industry today. And in recent years, that challenge has expanded exponentially.

For evidence of this, one can simply look to the Permian Basin, which generates 11 million barrels of produced water every day. The threats posed to the ecosystem by the surplus—largely due to high salinity levels and other contaminants—simply cannot be overlooked.

In recent years, in response, oil and gas producers have searched for ways to more effectively detect water leaks in their infancy, and thus to minimize problems before they can spiral out of control. To that end, one solution in particular has proved itself indispensable: AI-powered geospatial analytics.

The perils of produced water

Before explaining precisely what AI-powered geospatial analytics entails, we should take a moment to sketch the scale of the problem at hand.

The range of negative environmental and health effects caused by produced water would, if listed one by one, take up the entirety of this article—but a list of the most significant effects would include water contamination, contamination of streams and agriculture; damage to plants and aquatic life, and the generation of toxic substances like arsenic and radium, as well as carcinogens and other toxic chemicals.

One might ask: can’t this water simply be treated? Well, yes: but it’s not so simple. For one thing, the treatment process can be incredibly expensive. For another thing, this treatment process needs to be perpetually refined, as the exact properties of produced water are ever-shifting. There is no such thing as a “stable” treatment method in this context—proper treatment requires constant adjustment. And even if oil and gas producers had the resources to do this, they’d still have to reckon with the matter of public perception: for good reason, people are skeptical of drinking treated water.

AI-powered geospatial analytics are changing the game

For all of the above reasons, preventing produced water incidents before they can escalate is of paramount importance. And this is precisely what AI-powered geospatial analytics has proven itself remarkably effective at doing.

Key to this solution’s effectiveness is the reduced burden it places on manual identification. Previously, when oil and gas producers attempted to assess various problem spots, field assessors would have to roam vast stretches of land, with only their (fallible) eyesight to go on. This work was (and remains) expensive, time-consuming, and labor-intensive.

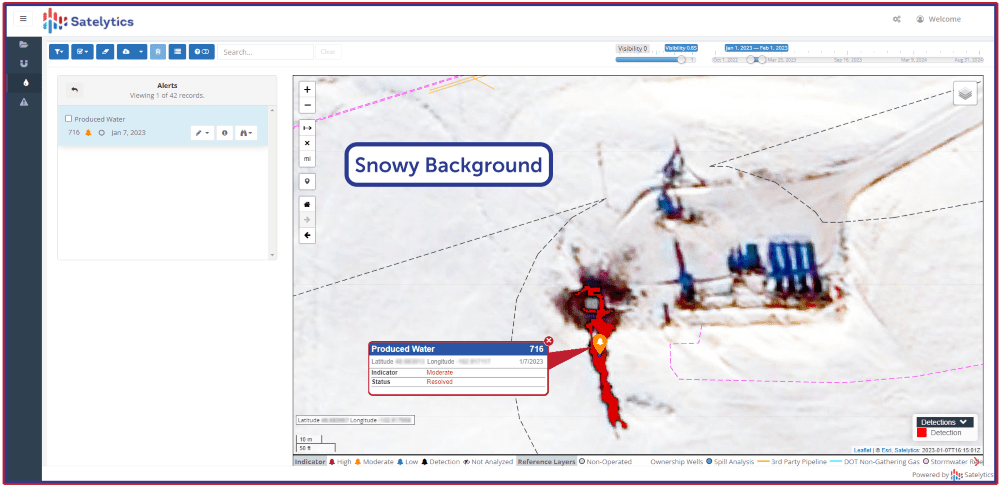

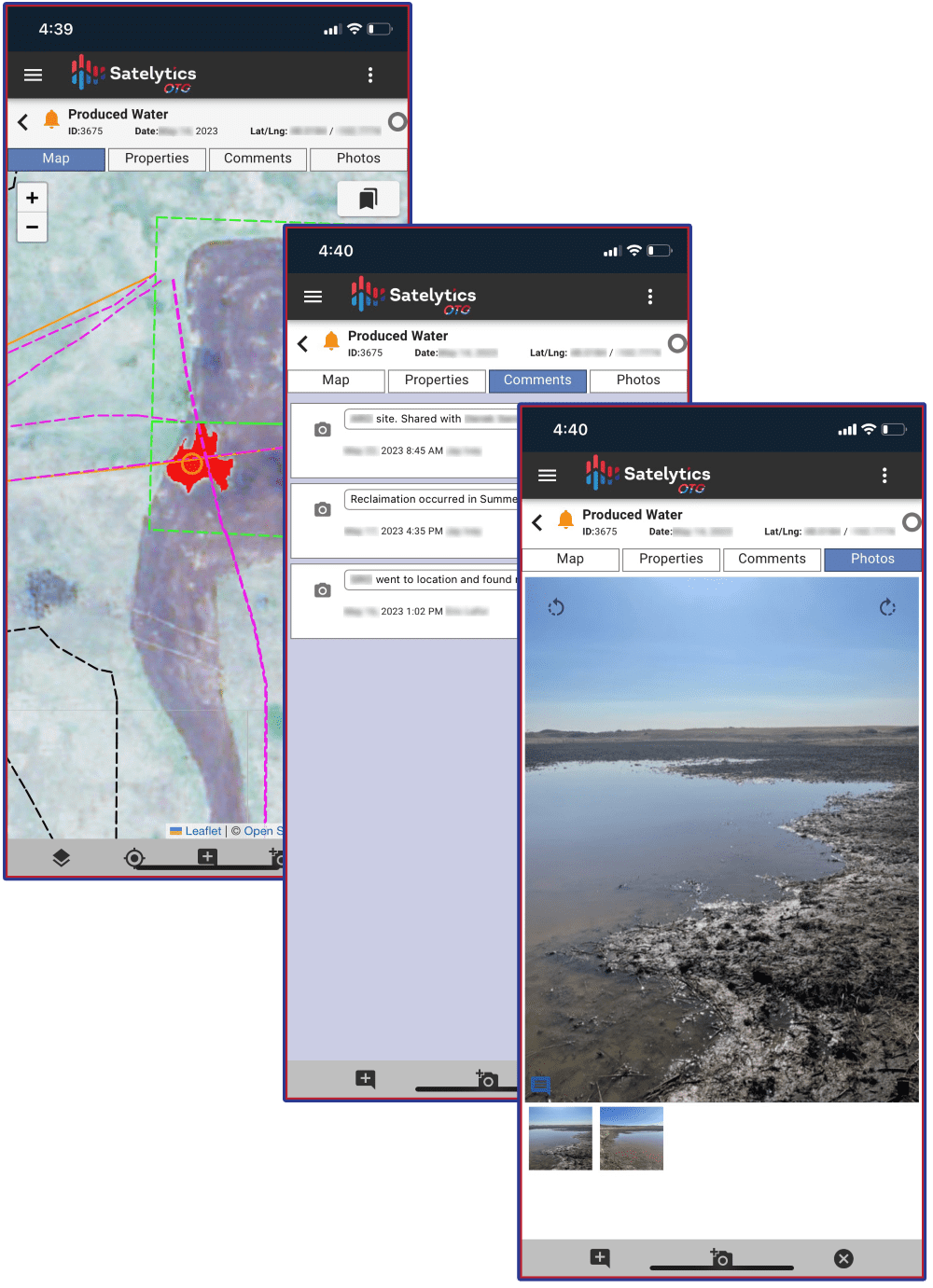

AI-powered geospatial analytics, by contrast, radically speed up and simplify this process. By deploying satellite imagery and advanced algorithms, the process allows oil and gas producers to rapidly survey the relevant terrain and identify areas showing signatures of chlorides and other chemicals typically found in produced water. From there, it can rapidly alert relevant personnel to any problems—allowing them to get a crucial head start on remediation.

Case Study: AI in the Bakken Formation

Recent work conducted in the Bakken Formation—a major oil and gas production region—vividly illustrates the benefits of this technology.

In recent years, a number of producers in the area have begun using AI-powered geospatial analytics to enhance their detection efforts. Notably, portions of the terrain in question were highly isolated: places where cell service is spotty or non-existent. This is a problem faced by oil and gas production sites all over the world, and in this case, it didn’t prove to be an obstacle: the companies were able to contract a non-connected setup factoring in the unique features of the landscape.

The result of this work was a leak detection accuracy rate higher than 89.93% over the course of three years, detecting both water and hydrocarbon signature capabilities. Similar results have recently been observed in Texas, which—after a surge in produced water spills—also began deploying AI-powered geospatial technology. The result in their case was the same: drastically higher detection rates and increased preventative action.

While it might not possess the name recognition of a problem like methane, excess quantities of produced water continue to plague oil and gas producers around the world. As oil and gas companies well know, the environmental and human costs of this produced water are too serious to ignore. While older, manual methods of detection still have their place, but going forward it is clear that AI-powered geospatial analytics represents the new gold standard in leak detection.

Sean Donegan is the President and CEO of Satelytics. He brings over thirty years of technology and software development experience to the company. A dynamic leader, Sean’s career has been focused on building companies through creativity and innovation, recruiting highly effective teams to solve customers’ toughest challenges. Sean founded or owned four successful software companies, most recently Sean Allen LLC which was focused on predictive analytics in the oil & gas marketplace.

With his energetic leadership style, Sean has always believed in building talented teams whose members are laser-focused on problem-solving, results, and financial objectives. These qualities were illustrated during his 15-year tenure as CEO of Westbrook Technologies, Inc. where he transformed a failing enterprise into a highly profitable document management software global leader with customers in 52 countries. Sean earned an undergraduate degree from the University of London and a postgraduate professional qualification from the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants. Sean lives in Hunting Valley, Ohio.