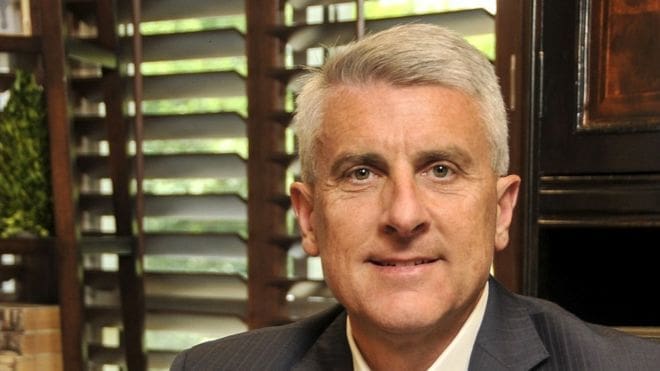

Rusty Hutson Jr is the boss of fast-growing US energy firm Diversified Gas & Oil.

The BBC’s weekly The Boss series profiles different business leaders from around the world. This week we speak to Rusty Hutson Jr, founder and chief executive of US energy firm Diversified Gas & Oil (DGO).

In the end, Rusty Hutson Jr couldn’t escape the calling of the family trade.

Born and raised in a blue-collar household in the oil and gas fields of West Virginia, his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all earned their livings in the energy sector.

They worked at the wells, and on the pipelines, putting in a hard shift of manual labour, day after day, year after year, to provide for their families.

During his summer holidays from high school and then college, Rusty would go to work with his dad.

But when he became the first Hutson to graduate from university, in 1991, he decided he wanted to do something completely different with his life.

“I decided that going into oil and gas was about the last thing I wanted to do,” he says. “I didn’t want a part of it when I got out. It’s really hard work.”

So armed with an accountancy degree from West Virginia’s Fairmont State University he went off to have a successful banking career for the next decade, ending up in Birmingham, Alabama.

But as the years progressed, Rusty says it started to nag at him that he hadn’t followed his dad into the family industry.

“West Virginia was a tough state when I was growing up. Still is,” he says. “And there were two kinds of people – you either worked in coal, or you worked in oil and gas. It was a generational thing – if your dad and grandfather did it for a living, then you did it.

“And as the years progressed I increasingly felt drawn back to that world. I also had this desire to build something, to do something entrepreneurial.”

So in 2001, aged 32, Rusty bought an old gas well back in West Virginia for $250,000 (£200,000). He raised the money by remortgaging his home.

“It was a small old well, it had been in production for years, but it was like gold to me,” he says. “I spent the next four years still also working in the bank, but any spare time I had I’d fly up to West Virginia to work alongside the one well tender that I had back then.”

Fast-forward to today, and Rusty’s company, DGO, now owns more than 60,000 gas and oil wells across West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee, a region called the Appalachia. Employing 925 people it has annual revenues of more than $500m. Some 90% of its operation is natural gas, with 10% oil.

The company’s business model is a very specific one – it doesn’t do any drilling to find new oil and gas reserves. Instead it buys up old oil and gas wells that bigger producers no longer want, because the initial large flow levels have fallen to low volumes.

“They don’t want these old wells, but the average remaining life on most of these wells is 50 years,” he says. “So we can come in, run them very efficiently, and make money.”

Rusty says that DGO has been greatly helped by the so-called “dash for shale” in the US over the past decade, whereby oil and gas firms gave up traditional oil and gas wells to switch to fracking instead.

In very simple terms, unlike traditional wells where oil and gas is sucked up, fracking involves first injecting a high pressure mixture of water, sand and chemicals into shale rock. This fractures the rock, and allows the removal of vast quantities of oil and gas that wasn’t previously accessible.

Rusty says the industry-wide move to fracking, and its higher production volumes, meant that DGO has been able to buy thousands of old, but still productive, traditional wells cheaply, and rapidly expand the business.

To help raise funds for continuing expansion, in 2017 the company decided to go public and sell its shares on a stock exchange. In an unusual move for a US firm, Rusty chose the London Stock Exchange’s (LSE’s) Alternative Investment Market.

“We weren’t big enough at the time to float in the US,” he says. “And I didn’t want to go down the private equity route because I didn’t want to work for somebody else, and try to earn back some of the percentage.”

DGO is now in the process of moving up to the Main Market of the LSE.

Energy sector analyst James McCormack of Cenkos Securities says that DGO’s strategy of “acquiring low-cost, long-life, low-decline [oil and gas] production” is “a virtually unique proposition”.

He adds: “Under Rusty’s leadership, DGO has grown rapidly since its IPO (initial public offering) in February 2017, increasing production 20 times and reserves 23 times.”

Fellow energy analyst Carlos Gomes of Edison says that DGO is now the largest conventional gas producer in the Appalachia region. “The company possesses long-life, low operational cost, mature producing assets that generate very stable cash flows,” he adds.

The long-term plan at DGO is to keep buying wells to replace any that eventually come to the end of production, and Rusty says the firm is now looking to expand into other regions, such as down in Texas.

In the more immediate term, he says that he is relaxed about the big falls in oil and gas prices since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, both because he has long-term “hedges” or agreements in place on what price he sells his production for, and because his business operates more efficiently than its larger rivals.

He can also turn to his dad for help and advice. His father, Rusty Sr, is the supervisor for the company’s northern West Virginia operation.

“He’s 72 and he just absolutely loves it,” says Rusty. “Does he try to tell me what to do? Oh, absolutely.”

Sourced through Scoop.it from: www.bbc.com