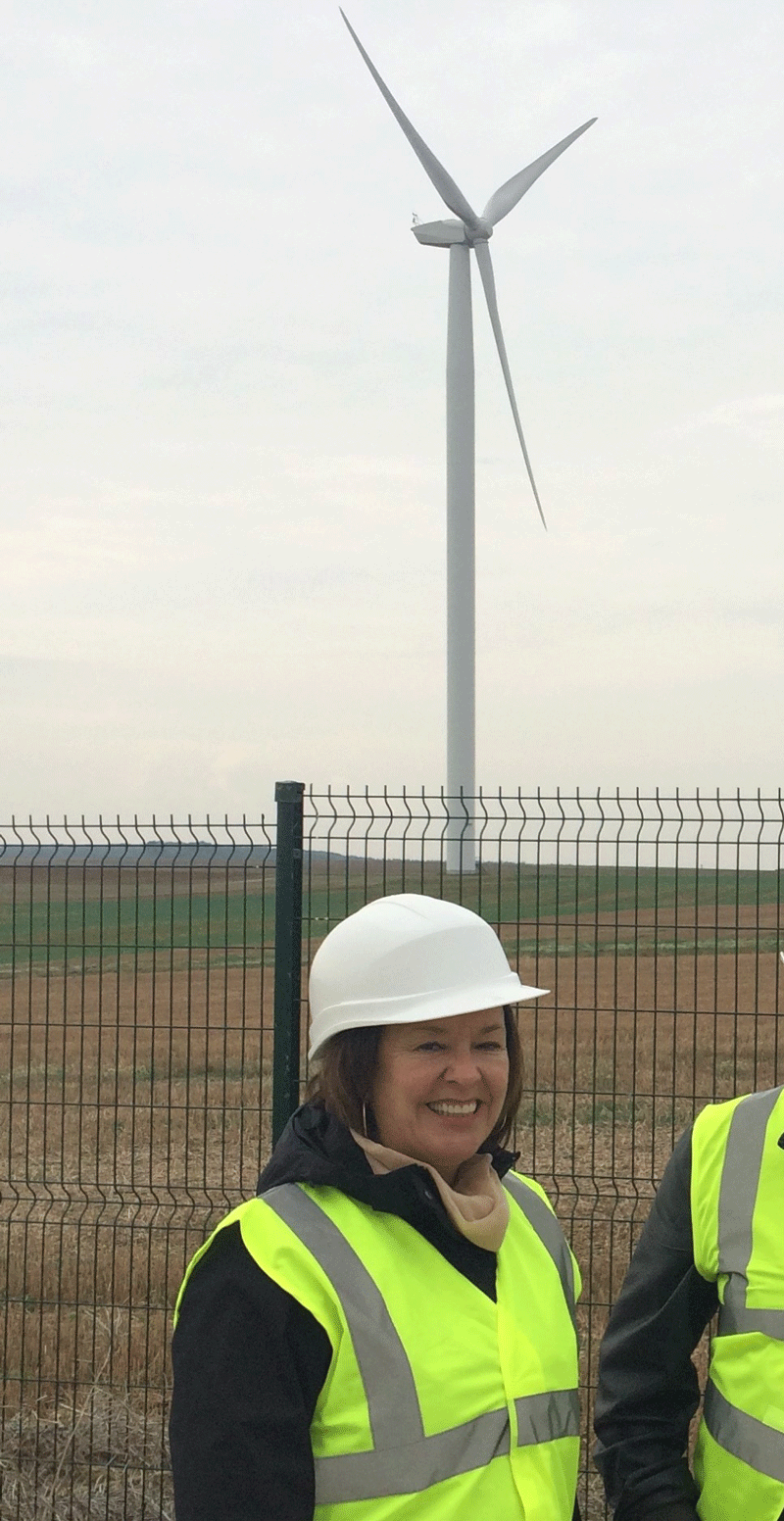

“[It] created a deep and lasting impression on me,” Dany St. Pierre says, as she recalls seeing her first offshore wind park in Denmark in 2005. St. Pierre, who heads up Women of Renewable Industries and Sustainable Energy (WRISE), a 501(c)3 charitable organization that promotes the advancement of women in renewable energy, says, “These very large and powerful wind turbines are part of the solution to climate change, and this experience convinced me to pursue my career in the renewable energy sector, since it is here to stay.”

Recent developments in the energy industry make it clear that offshore wind is a growing sector, with an increasing number of opportunities for women and minorities at various levels of skill and expertise.

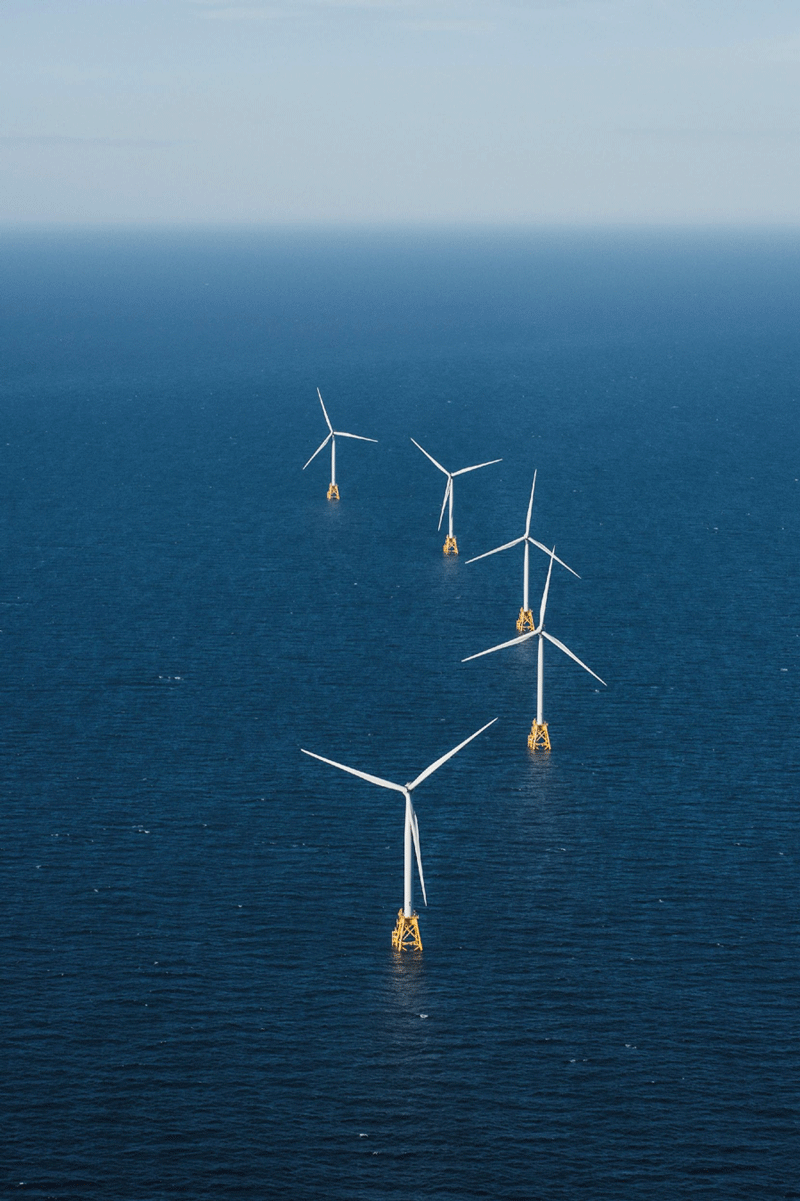

For many years, the U.S. lagged behind Northern Europe and the U.K. in embracing the potential of wind power. That changed in 2016, when Block Island Wind Farm (BIWF) off the coast of Rhode Island became fully operational.

The first – and, to date, the only – operating offshore wind farm in the United States, BIWF encountered some pushback during the planning stages, including a lengthy and controversial permitting process, and resistance from some Block Island residents, who claimed the turbines were unsightly and might affect migratory birds.

With those hurdles cleared, BIWF now provides 125GWh of electricity per year, reducing energy costs on Block Island by around 40 percent. The success of BIWF has paved the way for other offshore wind developments.

Also off the coast of Rhode Island, work is proceeding on the proposed Revolution Wind project, a partnership between National Grid and Ørsted U.S. Offshore Wind that, as envisioned, is 13 times larger than BIWF, and is projected to generate enough clean energy to power 270,000 homes. Projections show several million tons of carbon dioxide emissions being eliminated due to the fossil fuel-based electricity sources Revolution Wind will replace.

Offshore wind has some advantages over land-based wind energy. Coastal winds tend to be more constant, whereas inland wind energy projects have sometimes been unreliable due to intermittent winds. And coastal winds typically rise in the late afternoon to early evening when customer energy demand is at its peak.

Coastal states like Rhode Island, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and others, then, are ideally positioned to take advantage of the maturing technology and investment in the offshore wind energy sector.

In a January 2020 Executive Order, Rhode Island’s first female governor, Gina Raimondo, who took office in 2015, set a goal for the state to achieve 100 percent renewable electricity by 2030, building on a prior goal she had set to increase Rhode Island’s clean energy portfolio tenfold by the end of 2020. Revolution Wind, slated to be operational in 2024, will get the state much of the way there.

Costs of offshore wind are decreasing, as initial investment in infrastructure and development is offset by energy savings, and as the technology begins to mature. Recently, jobs in clean energy have become a talking point for both energy executives and elected officials, particularly during the uncertainty around COVID-19 and the worst economic recession the U.S. has seen in generations.

Rhode Island Energy Commissioner Nicholas Ucci said the energy sector is a bright spot and that it employs 16,348 workers in the state (with the majority being employed in energy efficiency). “While the coronavirus pandemic has affected all industries, we fully expect the clean energy industry to rebound,” he says. “The Revolution Wind offshore wind project, scheduled to begin construction next year, is expected to create more than 800 construction jobs, as well as hundreds of support jobs further down the offshore wind supply chain – these include careers in science, oceanography, offshore wind technology, transportation, professional services and more.”

Laura Morton, senior director of policy and regulatory affairs, offshore wind, at the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), says job growth in the sector is widespread and robust. “With up to 83,000 jobs in the pipeline over the next ten years and more than 70 different types of occupations needed to plan, develop, operate and maintain offshore wind farms, women will continue be at the forefront of the clean energy revolution and play a leading role in the growth of this brand new energy industry for the U.S.”

Ucci echoes this sentiment, “These emerging and dynamic clean energy industry jobs represent exciting new opportunities for women entering the clean energy workforce and for those already engaged and seeking new challenges.”

All of these developments add up to good news both for women in the industry and those looking to transition to clean energy jobs. It is estimated that 21 percent of those employed in the offshore wind sector are women, a figure that is higher than that of women in oil and gas (15 percent), but less than solar where women make up about 26.3 percent of the workforce.

St. Pierre, who describes the mission of WRISE as seeking to promote the advancement of women to achieve a strong diversified workforce and support a robust renewable energy economy, says, “I encourage women who aspire to have a long career in an exciting energy sector to give a look at the many offshore wind companies’ job postings as well as the free job board of WRISE.”

Other notable developments for women in the wind energy sector include a partnership between Ørsted North America and the University of Delaware, launched in 2018, that led to the establishment of the Offshore Wind Skills Academy (OWSA), which offers training and certification in a variety of offshore wind essential skills.

Ørsted recently announced the appointment of three women to the Board of Trustees of its Pro-NJ Grantor Trust, a $15 million fund established to offer New Jersey-based small, women- and minority-owned businesses support in retooling to enter the offshore wind industry. Implemented ahead of Ocean Wind, a planned 1,100 MW offshore wind farm that will serve New Jersey, the Trust was announced this fall and will make its first grants in early 2021, providing funding for infrastructure resiliency improvements to New Jersey Shore communities. Ocean Wind is expected to provide a significant number of permanent jobs throughout coastal New Jersey.

Some analysts estimate wind energy could become competitive with fossil fuels in terms of cost within the next 10 years. With Ocean Wind and Revolution Wind projected to be fully operational by 2024, and other new developments no doubt following suit, it’s plain that wind energy – and in particular offshore wind – is a sector to watch, especially as the “Blue New Deal,” proposed by Senator Elizabeth Warren (D – MA) and others, gains momentum.

The fact that there are a number of women in leadership in wind energy will help attract other women to the sector. In October, Ørsted North America Offshore named Patricia DiOrio, former vice president of U.S. Strategy with National Grid, head of project development. DiOrio, an East Coast native, says the appointment strikes a “personal chord” for her and expressed excitement at playing a part in Ørsted building the offshore wind industry in the U.S.

Morton sums up the big picture. “Reaching the American offshore wind sector’s massive economic potential will require workers of all types and backgrounds, including those with experience in legacy energy technologies, as we work together to bring clean, affordable electricity to population centers up and down the U.S. coasts.”

Headline photo: Gov. Gina Raimondo signing the executive order January 17, 2020, to advance a 100 percent renewable energy future for Rhode Island. Photo courtesy of State of RI.

Reprinted by permission. This article originally appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of OILWOMAN Magazine.

Kris Herndon is a writer of both fiction and non-fiction whose byline has appeared in The New York Times, Reader’s Digest, Magazine, Entrepreneur, Wired, Metropolis, Think, Stop Smiling, Paste, Art Papers and Architecture Boston, among others.